What Happens to Your Data When You Die in Pakistan?

Your body is buried. Your data isn’t.

The texts you never sent. The photos in your cloud. Your fingerprint, your face — locked in government databases. Your location history, your digital shadow — still pulsing across servers long after you’re gone.

In death, your physical self disappears but, your digital self lingers — unclaimed, unprotected and exposed.

In Pakistan, there’s no apparent law about what happens next. No rule to delete your data. No process to transfer control. Most families are left in the dark. Most platforms stay silent. And the state? Ambiguous at best.

And that’s not just eerie. It’s dangerous.

Here, where law struggles to keep up with technology and grief is entangled with bureaucracy, the digital afterlife isn’t just a philosophical dilemma. It’s a legal void. A security risk. A family’s unanswered question.

We’re racing toward digitization. But we’ve left one question behind: Who owns you when you’re gone? When the state, corporations, or strangers hold more of you than your family ever did — how do you disappear from a cloud that was never yours to begin with?

This isn’t science fiction. It’s already happening.

And the ghosts are piling up.

The Legal Vacuum Around Digital Death

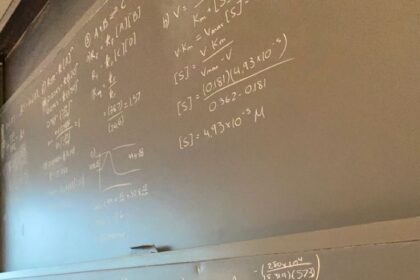

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 20231

It has 58 sections and 44 pages — and barely a word about what happens to your digital identity after death. Death is mentioned once.

Article 27 — titled “Right to Nominate” — allows a person to choose someone to act on their behalf after they die. It’s the only part acknowledging that the digital self doesn’t just vanish with the body.

There is no protocol for what happens if no nomination is made. No guidance for families trying to access the cloud-locked archive of a loved one. No mandate for companies to acknowledge death. No mention of the state’s role. The law gestures at legacy, but refuses to engage with loss.

The rest of the bill imagines only the living. It treats death as a technicality, not an inevitability. That failure is dangerous in a country like Pakistan, where even the living rarely knows—let alone are granted their rights.

Families struggle to memorialise profiles, retrieve photos locked behind accounts or even deactivate accounts or numbers. Without clear laws, platforms are free to treat the digital remains of Pakistanis as abandoned property.

And that’s the reality: in the eyes of the state, death ends the contract — not just with platforms, but with protection.

In a country where data is already unsecured, exploited, and politicised, the dead become easy targets for misuse. Their identities can be recycled. Their messages taken out of context. Their dignity violated without consequence.

PECA 20162

The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), 2016 was supposed to be our safety net — a shield against cybercrime.

Its key sections —

- Article 11: Electronic forgery

- Article 12: Electronic fraud

- Article 14: Unauthorised use of identity

- Articles 18–19: Offences against dignity and modesty

— offer strict punishments: multi-million-rupee fines, years of prison time.

But a closer look reveals a fundamental flaw. The law hinges entirely on the idea of an “aggrieved person.” A complaint must be filed by the victim, or, in the case of minors, their guardian. The framework is entirely reactive — and exclusively for the living.

What happens if someone steals the photos of a dead woman to create fake social media profiles? If deepfake pornography is generated using the face of a deceased journalist? What if an activist’s legacy is erased, rewritten, or twisted through selective deletion?

The law falls silent.

There is no mechanism for posthumous grievance. No right for families to file on behalf of the deceased. No clause imagining the possibility of digital harm beyond the grave.

In theory, these crimes still exist. But without a living complainant, they cannot be pursued.

This isn’t just a legal loophole — it’s a failure of moral imagination. It assumes that once someone dies, their dignity can no longer be violated.

But online, death isn’t an ending. It’s a frozen vulnerability, and PECA doesn’t cover it.

The 2025 PECA Amendment3

In 2025, Pakistan introduced amendments to PECA. It marked the birth of a powerful new regulatory body: the Digital Rights Protection Authority (DRPA).

- It can penalizeplatforms for failing to remove content.

- It can demand platform compliance with national laws.

- It expands the scope of who can file a complaint — from just the victim to any person with substantial reason to believe a cyber offence has occurred.

The language is broader, more aggressive and more regulatory. But its gaze is still on the living.

There is no guidance on who can act in the interest of a deceased person’s digital estate. No obligation for platforms to respond to family requests. No authority granted to the DRPA regarding the dead.

All of this reveals a larger philosophical failure in Pakistan’s digital lawmaking: a failure to distinguish between the user as a legal subject or as a human being. Our current frameworks treat digital presence as a function of activity, not of personhood.

Can the DRPA become a future watchdog for posthumous digital rights? Technically, yes. Legally, not yet. Morally, it must.

Bureaucratic Limbo

In a Facebook post4, a man from Karachi recounted the bureaucratic spiral he faced after his wife’s death. He submitted her death certificate to her bank, United Bank Limited (UBL), and was told the account would be closed.

Two months later, he returned with NADRA’s Succession Certificate — an official document listing verified heirs. But the bank demanded an Heirship Certificate, an indemnity bond and several other documents. When he asked about the difference between a heir and a successor, the branch manager simply said that it’s the policy of the bank. The process would take at least three more months.

The question wasn’t whether the woman had died. It was which version of death the system would accept — and how many times her family would have to prove it.

This is the reality of digital death in Pakistan: fragmented documentation, siloed institutions, no shared protocol.

- NADRA issues the Succession Certificate, after biometric and legal verification.

- Courts or provincial authorities may issue Heirship Certificates, often treated as separate.

- Banks often require indemnity bonds to guard against future disputes.

Each institution makes its own rules. None of them trust each other’s documents.

There is no central database. No communication between banks, courts or NADRA. No standard for what constitutes legal proof of digital ownership or access after death.

Even when the law technically supports inheritance, even when proofs exists, the system fails to transfer digital control. Even when all parties agree someone has died, the bureaucracy doesn’t know who has the right to step into their digital place.

This confusion is more than red tape — it’s an emotional and psychological harm.

Grieving families are forced to relive loss through repeated documentation, retelling, reapplication. Banks cite “policy.” State institutions deflect responsibility. No authority exists to resolve cross-platform disputes or streamline access.

Meanwhile, the digital lives of the deceased — from bank accounts to data archives — remain in limbo.

NADRA, Biometrics, and the Dead

Between 2019 and 2023, at least 2.7 million Pakistanis had their personal data compromised5, according to a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) report submitted to the Interior Ministry.

The JIT discovered that NADRA offices in Karachi, Multan, and Peshawar were allegedly linked to the data leak. The report also indicated that stolen data had surfaced in Argentina and Romania.

It can be chilling: identity theft, biometric fraud and cross-border data flows. The stolen data could be used to open bank accounts, acquire SIM cards, impersonate individuals online, or even surveil families — all without the victims ever knowing.

NADRA claims to have upgraded its cybersecurity infrastructure. But the fact that millions of citizens were exposed silently over five years reveals something deeper than a security failure. It reveals the structural opacity of Pakistan’s data regimes — particularly when it comes to what happens to your data after you die.

When someone dies in Pakistan, their Computerized National Identity Card (CNIC) is cancelled through NADRA. However, what happens to the fingerprints, facial scans and biometric authentication records attached to that identity remains unknown.

No official document clearly explains whether this data is deleted, anonymized, or retained — and if so, for how long, or for what purpose.

The 2025 National Registration & Biometric Policy Framework drops a clue:

“101,000 deceased citizens, marked as ‘deceased’ in CRMS, were verified biometrically from telecom systems after their recorded date of death.”6

This statistic is quietly explosive.

It suggests that biometric data — fingerprints, facial scans — remains intact and usable even after a citizen is declared dead. Whether this retention is intentional, lawful, or even monitored is never explained.

This is not just about leaks or inefficiencies — it is a crisis of biometric sovereignty. In life, citizens are asked to surrender their most intimate markers — fingerprints, retinal scans, face geometry — to access basic services. In death, they are given no assurances about how that data is stored, used, or destroyed.

There is no published biometric deletion protocol. No right to posthumous erasure. No family access to digital remains.

The fact that 101,000 deceased individuals were biometrically verified by telecom systems after their deaths isn’t just a quirk — it’s a warning.

In a system without deletion or transparency, death does not sever your relationship with the state. It simply renders you voiceless therein.

Social Media Afterlife

Social media platforms like Facebook, Google, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter) offer tools to handle the accounts of the deceased—but these tools are patchwork, corporate-controlled and often difficult to access.

Facebook lets you appoint a legacy contact7 who can pin posts or update a profile once it’s memorialized, they can’t log in or read messages. Google lets you pre-assign someone access8, but grieving families must rely on what was—or wasn’t—set up in advance. Instagram9 and X10 require paperwork to memorialize or remove accounts, access to content is limited and login details are not shared.

Crucially, none of this is governed by Pakistani law. The fate of a person’s digital remains is determined by opaque corporate policies, not enforceable legal rights. Families are left negotiating grief with algorithms—pleading with platforms, navigating silence.

Unlike physical estates, there is no legal right to inherit, transfer, or even delete a loved one’s online presence. The user dies. The platform decides what lives on.

The Risks: What Happens When the Dead Are Left Unprotected

When someone dies, their digital life shouldn’t turn into a free-for-all. But without clear rules, that’s exactly what can happen.

Fake accounts. Stolen credentials. Financial scams in the names of the dead.

Families, already grieving, are locked out of accounts, denied closure, and forced to relive their loss through bureaucracy and impersonation.

And it doesn’t stop with email or passwords. It reaches into the body itself.

Biometric data—fingerprints, facial scans, voice IDs—often remain stored in corporate or government systems after death. Without legal protections, this data can be reused, exploited, or even weaponized. What once confirmed your identity can, after death, become a surveillance tool.

This isn’t just a tech oversight. It’s an ethical crisis.

What happens to dignity when your face outlives your body in a database? What happens to modesty when your photos remain trapped in someone else’s cloud? What happens to consent when there’s no longer anyone to ask?

And beyond the policy failures lies a deeper cultural rupture. In many traditions, the soul’s peace depends on letting go. But what happens when the self—fractured into data points—remains trapped in servers and timelines, vulnerable to misuse, unable to fade?

What happens when we can’t bury the digital dead?

Can a soul truly rest when its digital shadow remains captive?

Your digital self doesn’t disappear when you do. It lingers—caught in gaps where laws don’t exist and systems don’t care. Without clear protections, Pakistan’s digital afterlife becomes a shadowy no-man’s-land where identities are stolen, memories exploited, and families left powerless.

This isn’t just a technical glitch or bureaucratic mess—it’s a wound. Families are shut out from their own memories, burdened with unanswered questions, and exposed to risks they never agreed to. The dead deserve to rest. The living deserve clarity. This is about respect—for those who have passed, for those left behind, and for the very idea of closure.

As we race into a digital future, we can’t ignore what happens when the screen goes dark. If we don’t claim ownership of our stories after death, someone else will—and it won’t be us or our loved ones.

These aren’t just data. They are real lives, real grief, and a call we cannot afford to ignore. They’re ghosts in the cloud.

And, they’re waiting.