There comes a canon event in nearly every Pakistani girl’s life—a moment rarely spoken of, but deeply felt. It’s when the tender dew of girlhood lifts with the morning sun, and the world, no longer kind in its gaze, begins to weigh her down with expectations. Not as an individual full of potential, but as someone whose identity must now be confirmed. Someone is expected to choose between two socially sanctioned paths. So she is placed at a fork in the road—two diverging lives that may occasionally overlap, but each demands more than it gives: marriage or career, domesticity or ambition. Rarely is there a third path. Rarely is there space for both.

This is the fork-road of identities, and it reflects a deeper structural truth: Pakistani society is far more invested in managing women than in empowering them. From early childhood, girls are taught to internalise a deep sense of duty—towards family, reputation, and community. They are not encouraged to ask, “Who am I?” but rather, “Who must I be for others?” Their worth is often measured not by their dreams but by their compliance.

Those who marry early are praised for ‘settling down’. Their identities become entangled in domestic roles—the good wife, the devoted mother, and the obedient daughter-in-law. They give their best years to caretaking, cooking, cleaning, and preserving family honour. And for many, this life becomes the full extent of what they’re allowed to be. They give and give to prove their worth until they are emptied—and still, it is never enough.

Those who pursue education and careers walk a different but equally narrow path. They become ‘working women’—a term that should be empowering but is often laced with suspicion. They are seen as too focused, too loud, and too independent—traits encouraged in men but penalised in women. Society questions their capacity to maintain a household, to ‘keep a man’, to fulfil their ‘natural’ purpose. And if they try to have both—a career and a family—they are met with impossible expectations. They must succeed professionally while shouldering the full weight of unpaid labour at home. They rise early, prepare breakfasts, drop children to school, work full-time jobs, attend meetings, manage in-laws, cook dinners, tutor homework, and collapse into bed—only to repeat it all the next day. Unlike their male counterparts, they are rarely offered support. They carry the burden alone and in silence.

At its core, this reveals a deeper truth: women in Pakistan are not seen as whole people. They are treated as roles to be performed—mother, wife, worker—never as individuals with inner lives, complex desires, and evolving identities. Men are allowed the luxury of growth, failure, exploration, and choice. Women, by contrast, are expected to live in service to an identity assigned to them.

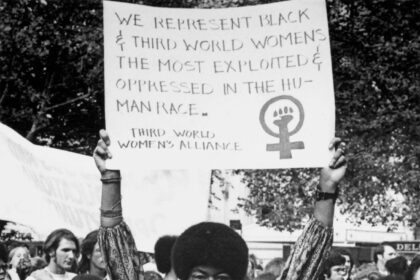

Sociologically, this is not just a division of roles but a hierarchy of expectations. Patriarchal systems don’t merely restrict what women can do—they shape how they are seen, what is expected of them, and how their value is measured. The working woman is not celebrated for her independence but penalised for it. The housewife is not honoured for her labour but taken for granted. In both cases, the constant is control—society’s need to reduce women to their utility.

So we must ask: What does it mean to be human in a system that sees you only as a function? A woman is not born to serve or to sacrifice—she is born to live. To think, to dream, to rest, to rebel, to become. But when her life is consumed entirely by responsibilities imposed upon her, when she is not allowed to rest or be seen beyond her service, she becomes a ghost of herself. This is not just a personal tragedy—it is a societal failure.

Within this system, the role of men must be interrogated too. Why is their contribution to home life still considered optional? Why are their smallest acts of “helping out” applauded, while women’s lifelong labour is expected as duty? If marriage is a partnership, why do so many women feel as if they are carrying both the physical and emotional weight of the relationship alone?

To build a just society, we must first dismantle the idea that women exist to carry it on their backs. We must stop romanticising sacrifice as a woman’s virtue and begin to recognise it as a symptom of systemic failure. True equality doesn’t begin with slogans—it begins with structural change: in homes, in workplaces, in laws, and in minds. Women are not symbols, not machines, and not silent labourers built to uphold tradition. They are people—full, breathing, thinking people. Until society treats them as such, it will continue to limit not only their potential but its own.

Let us remember: true strength lies not in the paths forced upon us but in those we carve for ourselves.