Childhood evolves with time. We all grew up listening to stories from our parents of how they used to play with other children in the street until their parents would drag them home at sunset. They would speak of how times were different back then, how it was safe to let children out on their own. A significant part of our generation, too, treasures similar experiences in their memory—either of playing in the street or in the local parks, which later came into fashion.

On any fine day in the summer of, let‚Äôs say, 2014, one couldn‚Äôt possibly get home without getting hit by the OG wrapped-in-white-tape baseball or unintentionally trespassing into a group‚Äôs game of¬Ýbaraf paani‚Äîchildren running around or just waiting for someone to free them by saying¬Ýpaani. Parks used to be so busy that the only way to get a turn on the swing was by getting a trusted adult to negotiate on your behalf, especially if the ones hogging it seemed to be outside your age group.

Childhood was simple and free back then. Whispers of “times have changed, the outside world isn’t safe” were too hard to hear over the sounds of children squealing, playing, ringing doorbells, and running away.

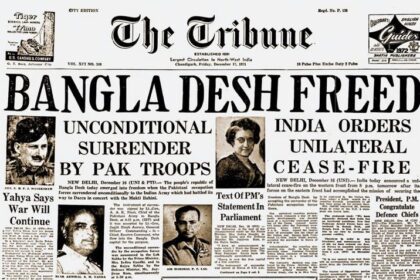

Somewhere around 2015, the news headlines started getting disturbing. Sunset became the ultimate curfew, and for some, it was the time for¬ÝAsr¬Ýprayer. Somewhere in the country, children were being stripped of their childhood bit by bit, and many families had sensed that. Playdates were separated because all of a sudden, ‚Äúthe outside‚Äù wasn‚Äôt safe anymore.

Kasur child abuse case shakes the nation.¬ÝOther rumors start to creep in. The house courtyard becomes the new playground.¬ÝZainab Ansari case. National outrage.¬ÝSilence haunts the streets and playgrounds.

Meanwhile, “funhouses,” which had already existed in urban areas—occasionally serving as places of recreation for children after a long day of shopping with parents—started getting popular as a safer alternative, though the visits could not be as frequent. Indoor play areas at restaurants and fast food places emerged as a new tactic to attract customers. Somewhere in between gated parks, fast food play areas, and indoor “amusement parks” (like Fun City and Sinbad’s), playtime for children of middle and upper-middle-class families found a new abode, all while being under the strict surveillance of anxious parents.

2020.¬ÝCoronavirus makes its way into Pakistan. Public spaces shut down. Now it was just the children‚Äîsome lonely, all bored‚Äîand their screens. Those who didn‚Äôt have one before the pandemic eventually got their hands on one as schools resumed online.

The older cool kids already had Minecraft. Roblox, Fortnite,¬ÝAmong Us¬Ýbecame the new playgrounds. For others, it was PUBG or Free Fire. Online predators emerged as a new danger. Some fell for the traps, while others played safe. This was the new normal.

As the world recovered from the pandemic and Pakistan recovered from its dark history of terrorism and widespread child kidnappings toward a new dawn, some streets started to echo with the sounds of squealing children again. Some local parks got their hustle and charm back.

Today, childhood has changed. The streets are not as crowded, the parks not as busy. Perhaps because the children of the pre-pandemic era are too old to play now, and children of the pandemic are too busy with their virtual playdates—communicating using vocabulary only they seem to understand.