There are performances that compel us to look, and then there are those that dare us to act. In 1974, Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 0 did both. For six hours, she remained motionless while audience members were invited to use one of 72 objects on her body however they pleased. Among the items were a feather, a rose, a knife, and a gun. “I am the object,” she declared. In that moment, she ceased to be an artist performing as a subject and rather became the subject of the audience’s psychology.

What unfolded in that gallery was not merely art. It was a psychological vacuum. A controlled environment where no social rules, no repercussions, and no expectations were imposed. It is easy to label it performance art. It’s harder to admit that it was a social experiment. And it’s even harder to confront what it uncovered: that in unstructured environments, humans do not default to compassion. They escalate.

What unfolded in that gallery was not merely art. It was a psychological vacuum. A controlled environment where no social rules, no repercussions, and no expectations were imposed. It is easy to label it performance art. It’s harder to admit that it was a social experiment. And it’s even harder to confront what it uncovered: that in unstructured environments, humans do not default to compassion. They escalate.

We tend to view morality as a fixed compass. But performances such as Rhythm 0 challenge that. They imply morality might be more like a contract, silently agreed upon and easily revoked when context disappears. At the start, audience members offered soft touches and gentle gestures. But as time passed and no boundaries were enforced, the behaviour deteriorated. Her clothes were cut. Her skin was slashed. One man placed the loaded gun in her hand and aimed it at her own neck. And when the performance ended and she began to walk toward them, they dispersed. The moment she reclaimed her personhood, they could not face her.

We tend to view morality as a fixed compass. But performances such as Rhythm 0 challenge that. They imply morality might be more like a contract, silently agreed upon and easily revoked when context disappears. At the start, audience members offered soft touches and gentle gestures. But as time passed and no boundaries were enforced, the behaviour deteriorated. Her clothes were cut. Her skin was slashed. One man placed the loaded gun in her hand and aimed it at her own neck. And when the performance ended and she began to walk toward them, they dispersed. The moment she reclaimed her personhood, they could not face her.

Abramović was not alone in blurring the lines between performance and provocation. A decade earlier, in 1964, Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece presented a similarly quiet invitation and revealed something equally loud beneath it. Ono simply sat on stage, silent and still, with a pair of scissors placed in front of her. One by one, audience members were asked to step forward and cut a piece of her clothing. Initially, the cuts were cautious. “Courteous.” Polite. But as the performance wore on, the cuts grew larger, more aggressive, and more intrusive. Some men sliced at her bra straps; others loomed uncomfortably close (Papazian, 2023). Ono never flinched. She allowed the violence to unfold without resistance.

Abramović was not alone in blurring the lines between performance and provocation. A decade earlier, in 1964, Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece presented a similarly quiet invitation and revealed something equally loud beneath it. Ono simply sat on stage, silent and still, with a pair of scissors placed in front of her. One by one, audience members were asked to step forward and cut a piece of her clothing. Initially, the cuts were cautious. “Courteous.” Polite. But as the performance wore on, the cuts grew larger, more aggressive, and more intrusive. Some men sliced at her bra straps; others loomed uncomfortably close (Papazian, 2023). Ono never flinched. She allowed the violence to unfold without resistance.

What made Cut Piece so unsettling was its elegance. There was no confrontation, only permission. And yet within that permission was an unspoken test: how far will people go when no one tells them not to? The performance was less about Yoko Ono and more about us—how we respond to vulnerability when it is presented as spectacle, how politeness can mask violation, and how the lack of structure reveals desire more than restraint.

What made Cut Piece so unsettling was its elegance. There was no confrontation, only permission. And yet within that permission was an unspoken test: how far will people go when no one tells them not to? The performance was less about Yoko Ono and more about us—how we respond to vulnerability when it is presented as spectacle, how politeness can mask violation, and how the lack of structure reveals desire more than restraint.

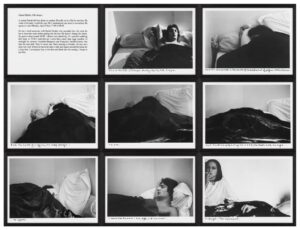

Where Abramović and Ono gave up control of their bodies, Sophie Calle gave up her privacy. Her work was not loud or violent; it was quiet, systematic, and disturbingly intimate. In one piece, she followed a man through the streets of Venice without his knowledge, documenting and recording his every move. In another, she invited strangers to share her bed while she interviewed and photographed them. And in her most invasive work, she gave someone unrestricted access to her personal emails, turning her real life into a written exhibit.

Calle’s art flips the power dynamic: instead of being physically acted upon, she offers up her boundaries and dares the audience to cross them emotionally. It is a different kind of exposure, one that is psychological rather than physical. In doing so she poses a piercing question: What parts or aspects of a person are we entitled to consume when we are led to believe it’s “for art”? And what does this reveal about us, that we rarely avert our gaze?

Then there is Tehching Hsieh, whose art is less about being seen and more about enduring. Over the course of five extreme year-long performances, he pushed not only the boundaries of his body but the very nature of time, repetition, and existence. In one piece, he punched a clock every hour for a year, both day and night, taking a photograph each time. In another, he spent his days living outdoors without shelter, speaking to no one. And in one of his most psychologically intense pieces, he tied himself to another artist with an eight-foot rope for 365 days, without ever coming into contact with her.

Unlike Abramović, Ono, or Calle, Hsieh did not invite the public to participate in his suffering. He made them observe it from the outside. But his work was no less revealing. In fact, it silently inverted the question: What happens when life becomes structure without meaning? Hsieh’s works demonstrate how routine can become confinement and how discipline without dialogue can cause a person to vanish in plain sight. The body does not break; the mind does.

Together, these performances constitute a body of work that functions less like art and more as a laboratory. They peel back performance and peer directly into human thresholds: for empathy, for cruelty, for boredom, and for voyeurism. They do not provide us with answers; they expose the circumstances and conditions in which our answers shift.

This is what makes them so unnerving and so necessary. In Rhythm 0, the most terrifying aspect was not what the audience did. It was the realisation that nothing stood in their way. No authority figure intervened. No internal compass held firm. No one in the crowd said, “Enough.”

These performances break the frame, and in doing so, break our sense of distance. We are not just viewing the art. We are implicated in it. Because when you take away the artist’s voice, the structure of the gallery, and the clarity of the script, what you’re left with is not performance.

You’re left with us.