It is a truth universally acknowledged that pretentious verbosity rarely gets the credit it hopes for. There is a particular breed of writer who believes that stuffing their sentences with five-quid syllables will perhaps make them an egghead; more often than not, it only makes them sound like an egg. And that is putting it lightly. Unfortunately for them, loquacity is not the best substitute for a good argument.

It is a magic trick often performed in political discourse, where otherwise simple truths cease to exist under the weight of convoluted language. Instead of confronting realities, we rename them, reframe them, or better yet, shroud them under a labyrinth of jargon, euphemisms, and circular reasoning. This essay isn’t just about bad writing. It is about writing that performs intelligence rather than demonstrates it. And it is everywhere.

How Obfuscation Protects the Powerful

An age-old game played by all stakeholders: governments, corporations, bad-faith intellectuals, self-proclaimed humanists, humanist-turned-political-contortionists, and our favourite, the armchair revolutionaries—forever lurking on the margins, rolling their eyes with the smug satisfaction of declaring everything broken beyond repair. A war crime becomes a “conflict,” the military establishment does not “intervene” in politics, it simply “ensures national stability,” it doesn’t rig elections, it simply engages in “pre-election management.” The more tangled the sentence, the less tangible the crime.

This kind of writing isn’t a fluke, but a strategic choice made to release collective responsibility. Clarity is dangerous because it demands accountability. When there are no metaphors to hide behind, and when the people understand what is done in their name, they are less forgiving. To avoid this objection, language is weaponized to confuse, and consequently, isolate the cause from the effect.

If you cannot define it, you cannot fight it.

The Pseudo-Intellectual’s Guide to Losing an Argument

Step one: When in doubt, complicate. If you are asked to explain your position, do not, ever, explain it in plain terms. Rather, open a rabbit hole of esoteric references and obtuse articulation. Never say “oppression” when you could have used “structural subjugation enforcing hierarchies of asymmetric constraints on agency.” Argumentum Verbosium, or 3000 words that could be summarized as “I do not like what you said, so I’ll just write a longer essay.” The world is your oyster, and you have a thesaurus at your fingertips. Make it count.

Step two: Replace verbosity with intelligence. If your argument does not sound like an excerpt from Black’s Law Dictionary (no hard feelings, I love the eleventh edition), then you are doing it wrong. Use three adjectives where one would suffice, with each reading like its very own encryption key. If anyone asks you to be clear, accuse them of “anti-intellectualism.” We did that at Oxford; it was a most stimulating experience.

Step three: Use terms like “ad hominem,” “straw man,” and “red herring” freely rather than engaging with the actual argument. While it might be a bit of a conundrum to use a logical fallacy incorrectly (a logical fallacy in itself, but who’s counting), it will certainly make you sound smart. Scout’s honour.

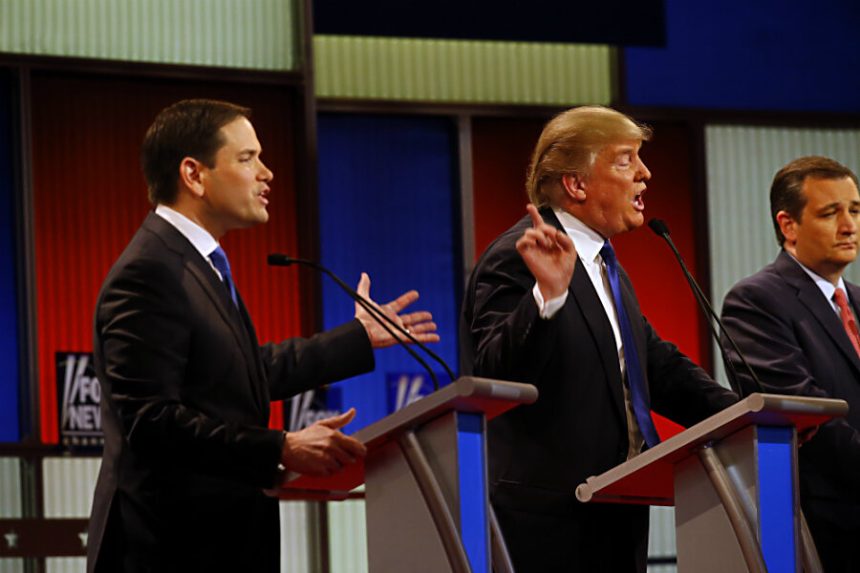

How Bad Writing Corrupts Political Discourse

Clarity is a radical act.

That is why the most dangerous thing about pseudo-intellectual writing isn’t just that it sounds like Kant and Hegel had an autistic lovechild, but that it deliberately excludes people—particularly other socioeconomic groups—from political dialogue. The more indecipherable a policy, the more immune it is to criticism. And cynics hate criticism; it is a silent agreement amongst the realist lot to always abstract a debate, but never be questioned in their rhetoric.

This is also how revisionism thrives. By taking a fact, burying it under a mountain of fancy words, adding a sprinkle of selective history, and making it inaccessible, you reduce the likelihood of more people questioning it, thereby evading accountability altogether. When politics becomes an exercise in linguistic gymnastics, it pushes people to disengage. Incomprehensible political writing makes for impossible political action. And nothing is more convenient for the brave sons of the soil than an audience too exhausted to fight back.

Call It What It Is: Bad Writing, Bad Arguments

A bad argument dressed in academic vernacular is still a bad argument. If it requires a dictionary or divine intervention to make sense, then perhaps it is time to reconsider its true purpose: not insightfulness, but evasiveness.

The ability to express difficult ideas in simple terms is not a weakness, but a skill. Orwell knew this. So did Baldwin and Roy. If your ideas are sound enough, then they no longer need padding. Bad writing is not a stylistic issue; it is an intellectual fraud masquerading as depth in order to serve as an instrument of control, ultimately aiding those who benefit from public confusion.

So let us call it what it is. Not intellectualism, not complexity. Just bad writing.