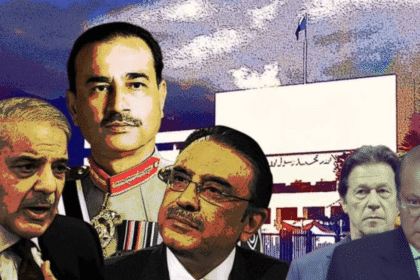

In 2025, the political environment in Pakistan is loud and empty at the same time. The people’s near-silent collective despair accompanies the commotion of unending political competition, protests, press conferences, and polarising talk shows. The ballot has become a habit rather than a hope for millions of citizens. Elections take place, the government changes, yet the reality experienced remains adamantly unchanged.

It is not just a crisis of politics; it is a crisis of confidence. The greater the amount of ritual the system undertakes in its democracy, the less believable it becomes in the eyes of the observers. This dilemma is what the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) described as the paradox of discontent with governance, not democracy: Pakistanis continue to hold onto the ideals of democracy, but they have lost trust in the actors and institutions that should enforce these ideals. It is a disillusionment that is deeply rooted in disinformation, economic anxiety, and a feeling that politics has lost touch with people’s day-to-day lives.

The Real Crisis of Pakistan’s Democracy

The Anatomy of Distrust

Rhetoric does not create trust, but predictability does. Once individuals can have reasonable access to fair treatment, timely services and a sense of justice, they are likely to place trust in institutions. The opposite has occurred in Pakistan. The government is perceived as distant and arbitrary. Citizens read promises of a fresh start, going over and over again in the manifestos, only to lose all sense in the bureaucratic fumes as soon as the cameras are switched off.

Such loss of trust is also ethical. Politics is no longer taken as a service to the populace; rather, it is now performance art — a theatre of slogans and accusations. Previously, digital media was assumed to democratise information, but it has instead increased cynicism. The Digital Rights Foundation noted that disinformation flourishes where institutions are least credible; the fake news sinks into the soil of the distrust of the population. That is fertile soil in the case of Pakistan.

In the meantime, the day-to-day business of government — municipal services, policing, taxation, dispute resolution — is still weak. The state rarely earns the trust of citizens. To most people, the government is merely an abstract entity seen on television or as a form of coercion to do things or face the consequences, not as a collaborator in the problem-solving process.

Why Local Government Matters

Could local governance serve as a point of reconnection for those who perceive national politics as unreachable? The idea is not new. Pakistan goes back to the pledge of devolution every few years to take power nearer to citizens, to make political rights come to life, and to return political rights to the real world. Article 140-A of the Constitution demands that the provinces come up with elected local bodies — a fact that democracy without localisation is a shallow one.

The foundation of local government is based on a fundamental principle: proximity breeds responsibility. Citizens can extract responses when they have a personal acquaintance with their representatives — when they see them at the market, at meetings of the community, etc. Exchange is not an institutional exchange but a human exchange. The issues that appear abstract on the federal level, such as a broken street light or a polluted water line, are concrete on the local level.

The experience of decentralisation in Pakistan, however, has been bumpy. Each regime has signed it with words only to compromise it. Political conveniences create and dissolve local bodies, reducing their term of office and denying them resources. The effect is that local governance has never had the time and freedom to develop into a believable system.

Still, the potential remains. An effective local government is able to serve as the initial phase of democratic mend because it will bring back visibility, not because it will resolve all problems. As soon as citizens can observe the government act, however humble this effort may be, they start believing once again that it makes a difference.

Restoring the Moral Contract

The greater is the psychological, rather than administrative, problem. The lack of trust in governance is not merely on issues of corruption or ineffectiveness but also disconnection. The Pakistani nation and nationals usually seem to exist in two different worlds: one is talking about policies and press releases, the other about load-shedding, inflation, and unemployment.

The local government, which operates at the intersection of lived experience and official authority, is capable of reducing that divide to a manageable size for crossing. However, mere decentralisation on paper will not achieve this. High standards of participation are required. Unless the citizens are regarded as active partners and not passive beneficiaries, local democracy will only remain a facade of bureaucracy.

Another significant finding by the Urban Institute study of the way citizens feel about local governance is that individuals believe systems that acknowledge their voice, even with flaws in results, are going to work. Trust is not made through transparency but rather through recognition. The citizens should believe they are being perceived and listened to, and can influence. It will imply participatory budgeting, transparent meetings, community audits, and transparent feedback loops — tiny gestures that restore belief in the shared project of governance.

Beyond Structure: A Cultural Shift

Effective governance can never be defined by laws or measures; it is a culture after all. The administrative ethos in Pakistan is still hierarchical, centralised and cautious of the participation of the citizen. The transition to a participatory model would require re-educating the ruled and the rulers.

In the case of officials, it can be understood as learning to share power, accept criticism, and judge success when citizens are satisfied and not when the bureaucracy is in control. To the citizens, it is their responsibility to attend meetings, keep to budgets, demand transparency, vote regularly, and be anti-apathetic.

Such cultural change is gradual, but it starts on the local level. When a councillor explains a budget at a meeting, when a mayor publishes municipal accounts on the Internet, and when people make a sanitation project jointly in front of each other, democracy stops being an ideal — it becomes reality.

Disinformation, Trust, and the Local Public Sphere

The polarised discourses of the national media space are nearly uncontrollable. With the assistance of local governments, it is possible to rebuild a healthier information ecosystem by creating community-based communication public bulletins, town halls, and verified online portals. These low-key sites have an opportunity to neutralise disinformation by being closer to their users and demonstrating more credibility: individuals are less inclined to accept crazy theories about systems that they are part and parcel of.

One of the OECD trust reports observed that misinformation thrives in areas where people lack direct experience with governance. On the other hand, cynicism immunises direct contact with responsive institutions. The cure to the disinformation that Pakistan is facing could therefore not come in censorship or regulation, but in credible local experience.

The Way Forward

Restoring trust in governance in Pakistan is not an issue of new slogans and institutional tinkering. It is the reaffirmation of the democratic pledge that government can be of and for the people and not just above them. National politics can not be redeemed by local government, but it can be humanised.

The development of local bodies financially, politically and socially is a point of entry to reform that is real to the citizenry. The intangible notion of the state may once more be made intimate when individuals start perceiving visible improvements in their streets, schools, and neighbourhoods.

However, it will demand bravery on the highest level: to decentralise the power in good faith, to allow local leaders to rise beyond the patronage system, and to have the strength to believe that democracy can be strengthened not by dominating, but by trusting.

Conclusion: Trust as the New Currency of Governance

The crisis of governance in Pakistan is fundamentally a crisis of imagination — a crisis of failing to visualise government as a relationship as opposed to government as authority. The alternative to that relationship can be found in local democracy, in which leadership is transparent, accountability is instantaneous, and citizenship is meaningful.

It is not to be a turning point in 2025, yet another national reform plan; it is not to be a turning point by the promise or broadcast, but by slowly, patiently building confidence on the ground. To trust citizens — and allow them to trust their government once more — is perhaps the most extreme reform that Pakistan can make.