There has never been a more intense struggle between man and the environment than there is right now. Though nature, in all its unadulterated beauty, has withstood countless storms, volcano eruptions, and extinctions over the ages, humans now pose the greatest threat to it. We’ve emptied rivers, destroyed forests, and contaminated the air in our unrelenting quest for advancement, choking the very life force that keeps the humans alive.

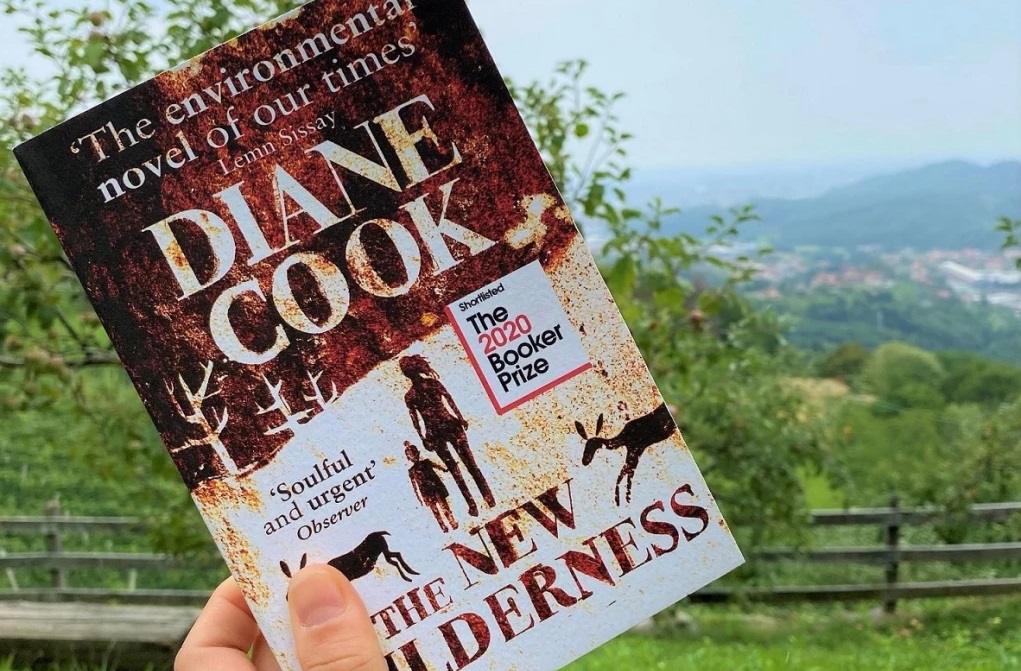

We are getting closer to a time when the wonders of nature will only exist in our distant memories, with each passing tree and the extinction of each species. One question looms large as we stand on the brink of environmental collapse: Will we destroy nature before it destroys us? The under-discussion book continues to explore this crucial issue. The end isn’t so much “nigh” as it is “come and gone” in Diane Cook’s Booker Prize-nominated debut novel, The New Wilderness.

All save a single natural preserve known as the Wilderness State, home to the last remaining populations of North American wildlife, and a tiny group of nomads known as the community have been overtaken by the collapse of civilization. We travel through this hostile land in the third-person perspective of Bea, a young mother who, in an unwise and impractical move, has chosen to enlist in an experiment in the Wilderness State to save her young daughter Agnes from the wasted city, where the air pollution has been killing her since the day of Agnes’s birth.

Bea is one of the first 20 volunteers in an experiment purportedly meant to discover if humans can coexist with nature without ruining it. The Manual, which lays out the rules for their existence and is controlled by the Rangers – whose whims the experiment and its participants are subject to – is the most valuable tool binding the community, of which she is a reluctant and pragmatically skeptical member, to meaning.

Instead of the scientists and experts that Bea’s well-meaning partner Glen had envisioned when he first founded the experiment, Bea’s fellow community members come from backgrounds that are incompatible with surviving in the Wilderness State. Their frequent mistakes are both costly and terrifying. The community’s politics becomes more self-serving and craven, as one might expect of common people thrust into extraordinary conflict, and as the structures they were taught to believe in come apart and threaten their existence, their individual goals diverge more and more from a shared purpose.

Diane Cook’s pessimism about the fate of our species remains unchanged from the time she published Man vs. Nature, an original and perceptive collection of short stories. One of her most striking themes in The New Wilderness is the destructive force of individuality and how ubiquitous human damage is — how the innate impulse to defend oneself undercuts the chance of progressive thought and community. Above all, it appears that she is wondering how we will treat each other if the climate crisis turns out to be the unquestioned central issue of our day. She shifts the narrative focus from mother to daughter midway through the book, exploring this theme through the turbulent relationship between Bea and Agnes.

First, we stand with Bea, who was raised in the dirty city and occasionally still yearns for it. Next, we support Agnes, who is a genuine nomad and has always called the Wilderness State home. The central tension of the book is the discord between the mother and daughter as they attempt to reconcile their differing perspectives of identity, community, and one another. The New Wilderness is filled with landscape, and Diane Cook’s writing is most effective when it focuses on the natural world.

The characters seem to respond quite awestruck or emotionally to the harsh, brilliant setting, but in my opinion, their ambivalence regarding so many other facets of life come at a cost. I think Diane Cook’s goal must be to show how her character has experienced things that most readers in the 21st century would find terrifying: a deadly mauling, a plunge into a chasm, and even the tragic stillbirth of a child whose personhood is tragically dismissed by a Ranger in one of the most moving scenes in the book.

The text must numb the readers and the narrative consciousness to these events. This is accomplished by warping features that would have provided us with a more accurate understanding of Bea, Agnes, and their surroundings, destabilizing our sense of time, and reversing perspective. The ambivalence of the characters unites them despite nothing else. They have an ill-defined, generalized view of one another. They don’t appear to recognize each other as real persons with vulnerabilities and pasts.

The intention behind this piece may be to demonstrate how individuals who are living with prospect of death don’t value one another’s uniqueness, yet the reader is inadvertently put at a distance. I often found myself wondering how individuals could remain such strangers for so long when thrust into such an experiment that drastically altered their minds, bodies, perception of time and societal norms.

Nevertheless, I’m sure that not every reader will find this distancing effect bothersome. In a time when it would be beneficial for every soul to have their stomachs turned by the prospect of the future Diane Cook imagines, the author masterfully manipulates a fast-paced, exciting novel to pose thought-provoking concerns. Personally, I was thankful for the ‘trip’.