On 16th January 2024, the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps launched missiles targeting alleged Sunni Baloch militants in Balochistan; in retaliation, Pakistan followed with Operation Marg Bar Sarmachar before de-escalation quickly followed. Such is the relationship that characterises Pakistan-Iranian relations today. Cautious, often suspicious dealings, punctuated with border skirmishes. A reality that makes people reminisce about when Tehran was ruled by one man, Shah Muhammand Reza Pahlavi, the last monarch of Iran.

The past is often remembered nostalgically, especially when one’s present is less than ideal, and that corresponds to Pak-Iranian ties. Under the autocratic tutelage of the Shah, centuries of cultural, historical, and religious ties manifested in an ironclad political and security alliance between Islamabad and Tehran. An assumption that is broadly correct but lacks nuance.

At the dawn of independence, Pakistan reached out to the world, eager to establish ties and be embraced as a sovereign state. Indeed, Iran was the first country to recognise Pakistan, and Shah Reza was the first head of state to visit it. However, during this period, the first hiccup between the two countries occurred: the Iranians asked Pakistan in early 1949 for a friendship treaty, which officials of the new state were eager to sign. Yet, the process of signing the agreement was strewn with misunderstanding, with Iranians first opting to consult with London to get the go-ahead, infuriating Pakistani officials in Karachi, who complained that:

“Pakistan is surprised that of them all, Persia should see fit to stand on a point of trivial technicalities.”

For the Iranians, it was a no-brainer to first assess London’s mood; the British dominated southern Iran for nearly a century during the colonial era. For Pakistan, it was tantamount to questioning the new nation’s sovereignty. Ultimately both countries signed a friendship treaty in May 1950.

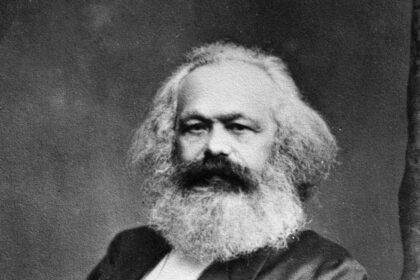

However, the awkwardness was quickly forgotten as relations became systemised between the two throughout the 50s. Pakistan and Iran grew closer on a common platform of anti-communist and pro-American policies. The Iranian Shah feared the communist influence in his country. Barely five years into his reign, the Soviets instigated separatist leftist uprisings in 1945-6, while an assassination attempt against the shah’s life was blamed on the Tudeh Party, the local communist party. Thus, the Shah was eager to craft close ties with America and countries sharing similar pro-West sentiments, something which he found in abundance among Pakistani officials, whose rivalry with India and pro-West orientation made them excellent candidates for a regional anti-communist pro-US bloc.

Iran and Pakistan signed several treaties during this time. In March 1956, a cultural agreement was signed; in 1957, an air-travel agreement; and on the 6th of February 1958, Pakistan and Iran signed a common border agreement, a crucial win for Pakistan amid border and land disputes with India and Afghanistan. Security ties were also strengthened when Pakistan and Iran joined the US-encouraged Baghdad Pact, later known as CENTO. All this was ameliorated by the fact that the then President of Pakistan, Iskandar Mirza, on account of his Iranian wife and Shi’i faith, enjoyed particularly good ties with the Shah. The Shah was so fond of Mirza that when the latter died in exile and Ayub, the new ruler, refused to allow his funeral in Pakistan, Reza Pahlavi had it conducted in Tehran.

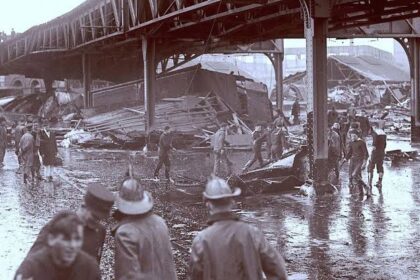

Ties under Ayub Khan entered even greater forms of cooperation after the anti-monarchist coup in Iraq in 1958, in which King Faisal and his family were executed. The Shah sought to strengthen ties with Pakistan as a result of paranoia, brushing aside the pro-Indian lobby in the royal court led by Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveyda. The Iranian Shah intervened in disputes between Pakistan and Afghanistan after the latter provoked diplomatic fallout over the Pashtunistan question and a failed invasion in Bajaur. The Shah’s ambitions as a regional power were immense, and he proposed a confederation between Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, with himself as head of state. The proposal wasn’t met with enthusiasm by Ayub Khan. Further, Iran and Pakistan, along with Turkey, signed an economic agreement under the RDC in 1964, and the Iranians supported Pakistan in the 1965 war. They even helped with military aid after the weapons embargo imposed on Pakistan by the Americans: the supply of 50 F-86 Sabres.

Nonetheless, relations during this period had major bumps as well. The Iranian Shah was locked in a regional struggle for dominance against Arab states in the Middle East. In particular, they feared the Arab revolutionary regimes inspired by General Gamel Abdel Nasser of Egypt. Thus, Ayub Khan’s infatuation with Nasser and the Pakistani people’s admiration of these Arab revolutionaries was a particular irritant, manifesting in such episodes as local Pakistani media calling the Persian Gulf the Arabian Gulf, only for the Iranian government media to retaliate by being sympathetic to India on Kashmir. A comical example being when Iranian authorities refused to print Ayub Khan’s book because it contained praises of the Egyptian leader.

The period of 1971-77 was the most juxtaposing era of relations under the Shah. In here, the personal sensibilities of the Shah showed how personalities affect foreign relations. Economic, military, and strategic ties reached their zenith between the two countries, yet private dislikes and clashing egos led to the cooling of ties. Iran once again helped Pakistan in its war against India in 71, with the Shah threatening to intervene if stability in West Pakistan was undermined. After Pakistan’s defeat, the Shah staked his country’s security and pushed the US to start rearming the Pakistani military. Yet after the 71 debacle, the Shah never saw Pakistan as an equal, and this attitude endlessly irritated Pakistan’s new leader, Bhutto. Relations between the two were warm during the period of 1971-73, with the Iranian monarchy supporting Bhutto, suppressing Baloch separatists by supplying Cobra helicopters, and jointly dealing with Daud Khan’s nationalist government in Kabul.

Economic assistance also reached its height, with Iran providing $800 million in loans between 1974 and 1976 and $700 million in aid in 1974 alone. Despite this, Bhutto’s quest to become leader of the Muslim world and upstart Iran as the US’s main regional ally upset the Shah. A personal comment by Bhutto against him during the latter’s visit to Nixon in 1973 shattered the goodwill between the two forever. The Iranian ruler further refused to visit the second OIC summit in Lahore where Muslim leaders had gathered. Furthermore, Iranians started developing relations with India in terms of nuclear cooperation, economic trade, and diplomatic dealings. While this alarmed Pakistan, Iranian closeness to India didn’t lead to less support.

Thus, at the end of Bhutto’s rule, Iranian relations cooled despite active support in the Balochistan conflict. The Shah would increasingly have a negative attitude toward Bhutto, who reciprocated, even accusing the Shah of foreknowledge of Zia ul Haq’s coup against him. When Bhutto was overthrown, however, the Shah threatened to cut ties with Pakistan if he was executed.

A threat that the Shah did not follow through on, due to domestic agitation, leading to his ouster in the Islamic revolution. Thus, an era of Iranian-Pakistani ties came to a close, which, despite the tensions mentioned, never again rose to the same level of friendliness seen under the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.