The human behind the label: When you conjure up the person who most strongly disagrees with you, what do they look like? A fire-breathing demagogue brandishing a sign that invalidates your entire belief system? An elitist snob with a college degree who has no grasp on reality? A keyboard warrior who couch rolls memes rather than literature?

Whatever image comes to mind, it’s important to remember that behind every disagreement, there’s a human being with their own story and struggles. It’s probably not someone you’d like to embrace on your porch, but it’s someone who shares the same human experience as you.

We are in an era where our political, moral, and ideological enemies are abstractions. Their outlines are sketched not by conversation but by curated snippets, algorithmic memes, and emotionally charged headlines. We know what they believe, or so it seems. We know what they vote for and what they tweet, so we know what they stand for. But what does their voice sound like when it’s a calming force? Their logic when it isn’t playing to win? Their tale before it was memed, clipped, and maligned?

I know from my own life that fear of the “other” is constantly fanned wherever knowledge fails. There is no governing notion of what fear actually is; it is not just an emotion but a political weapon, a marketer’s tool, a scaffold of identity. And what keeps it going best is distance. Literal, cultural, and intellectual distance. The one where we are never really together except in our fantasies.

Years ago, while leading a workshop on religious pluralism, I asked a group of high school students to physically position themselves on a freshly painted continuum on the floor, based on who they saw as ideologically opposing them. Their responses also came quickly: “homophobes,” “woke liberals,” “anti-vaxxers,” “elitist atheists,” “wealth-driven elites,” “extremists.” It was a buffet of outrage. When I probed to find out how many had ever spoken with someone on that list for more than five minutes, not online, not in the form of debate, but in the essence of listening, just a single hand went up. Out of 47.

This isn’t just anecdotal; it’s symptomatic. We’re all becoming caricature connoisseurs in the interim. A misfortune indeed.

There’s a growing tension in the world between the impulse to connect and the instinct to fragment. In uncertain times, identity often calcifies into opposition, where we define ourselves less by what we stand for and more by whom we stand against. When that happens, diversity stops being a source of wonder and starts feeling like a battleground.

This is not a Western phenomenon, nor is it a 21st-century construct. It has existed as long as tribalism has. However, today, the apparatus is more effective than ever. We’ve curated digital ecosystems feeds that feed our preferences and shore up our prejudices.

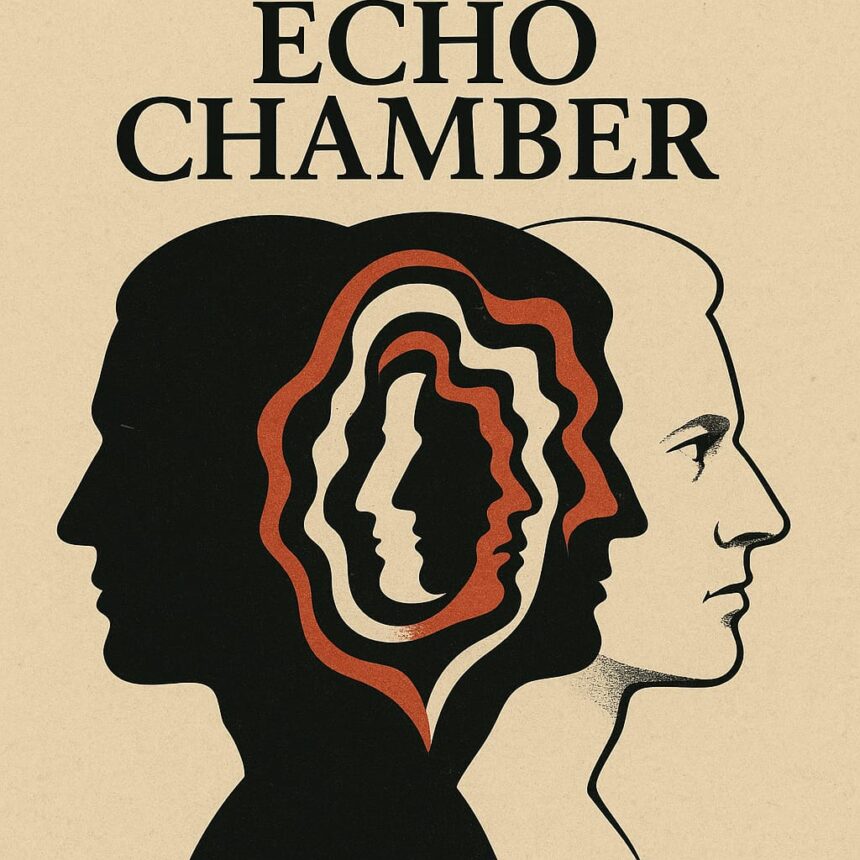

Social media, for all its utopian promises of connection, is effectively a self-amplifying hall of mirrors: a forum for our biases that grows an increasingly long and noisy echo chamber. And the more we dwell inside it, the more our responses ossify. Outrage becomes muscle memory: swift, rehearsed, and ready on demand. We no longer sift through nuance; we swipe, react, and reload. Nuance, once the mark of the thoughtful, now gets dismissed as pedantic. All in all, certainty performs better while performance performs the best.

The philosopher Martin Buber once wrote of the sacred “I–Thou” relationship, a way of meeting another human being not as a function, a type, or a target, but as a soul. A presence to behold, not a problem to solve. But in the world we now occupy, our posture has shifted toward “I–That.” The person across from us becomes a caricature, a symbol, an opponent to be neutralized. We do not recognise their burdens, only their badges. We do not ask, “Who are you?” but instead, “What are you?” The conversation is replaced with an elocutionary performance, labels often lobbed like grenades, and facts weaponized without context. And from there, the path to estrangement becomes paved in pixels.

And what do you do when that voice comes out behind the label?

Allow me to introduce you to Zahra, a veiled environmentalist in Michigan. A few years ago, she was asked to address climate education at a town council meeting in a conservative, predominantly white county. By the time she arrived, anonymous Facebook threads had attacked her for trying to “bring Sharia law through climate activism.” A radio host implied she was an agent of a subversive ideological saboteur. Then she took the podium and spoke, softly yet firmly, about composting, air quality, student-led sustainability projects, and the mood shifted. Afterwards, one man who had been wary of “liberal agendas” came up to her and said, “You remind me of my daughter.” That was all. No conversion, no dramatic change. Just one sentence. One fissure in the wall.

In June 2025, that very estrangement was addressed from one of the world’s most visible stages. Under the open sky of St Peter’s Square, with summer light pooling over centuries-old marble, Pope Leo XIV stepped before tens of thousands gathered in person and millions more online. His voice, both steady and unhurried, did not thunder. It rather invited.

What he offered that day was not merely a call to peace among nations, but a plea for human beings to remember how to face one another. He did not speak directly of politics or doctrine. Instead, he named a deeper ailment: “a spiritual estrangement from the world we share.” He spoke of how easily we have become strangers to those who live beside us, how fiercely we hold beliefs we’ve never tested, and how rarely we dare to ask someone, not what they think, but why they came to believe it.

He asked nothing lofty, only that we begin with honor of the other’s story, their struggle, their wounds. “Dialogue,” he said, “is not a strategy. It is a way of being. You do not listen to persuade. You listen to dignify.” And there, under the Renaissance dome, something rang ancient and authentic. In a time of snark and slogans, he was inviting the world to rediscover the slow work of humanization, the process of seeing each other not as opponents, but as fellow human beings.

The crowd did not erupt. It listened. And perhaps that was the point. No grand applause. No viral moment. Just the quiet possibility that if we began to meet eyes more often than we met headlines, the atmosphere might change. Not overnight, but slowly, like light softening the edges of a morning long overdue. This potential for change should inspire us all to take the first step towards understanding and empathy.

There is an adage that no form of prejudice has a remedy like that of proximity. And yet we currently organize our lives to prevent precisely that. We retreat to neighborhoods, digital and physical, where our beliefs are reflected. Our friends echo our values. Our feeds filter discomfort. Our bookshelves (wherever we stashed them, if we even still have them) are filled with titles that tell us what we already sensed.

I recall once sitting across from a man at a fundraiser who had posted xenophobic vitriol just weeks before. I almost declined the invitation. But destiny, so it seems, had us sitting next to each other. We talked for three hours, not about politics, but about our mothers’ cooking, our kids’ struggles in school, and the scourge of ever-increasing health care costs. As dessert came, we still did not see eye to eye, but I no longer saw a monster. I saw a man who grew up in an economically precarious environment, swept up by change, and craving certainty in a time of uncertainty.

Was he wrong? Often. Was I too? Maybe too much, if I were being honest with myself. But here’s what I found: when you insert a human being into the equation in your head, the calculus changes.

Of course, that is not to argue for a false equivalency. Some opinions are violent, oppressive, or based on supremacy. Dialogue does not mean agreement. No one should weaponize civility to silence pain. But there’s no denying that refusing to engage with humans at all is no improvement, especially when our resistance is cloaked in cerebral detachment, as though complexity absolves us from connection. It just hands the microphone to ideological absolutism on either end.

There is a quiet valor in choosing engagement. It requires us to sit in the discomfort of being misunderstood, along with the humility of admitting we are wrong. It asks us to show up not just with opinions, but with skin in the game to wager something of ourselves in the exchange. It requires that we substitute certainty for curiosity, but not just as an indulgence, a passive taste hit, if you will, but as a radical praxis for justice in a culture that thrives on polarization.

Let’s do a little thought experiment. Imagine someone you strongly disagree with invites you to tea. No cameras, no tweets, no imperative to “win.” Just a conversation. They ask you, sincerely, “How did you come to think the way you do?” And then they wait. No interrupting. No scoring points. Just listening.

Now, imagine you do the same.

Would you walk away transformed? Maybe not. Only, perhaps, you would not walk away so sure of their monstrosity. And that is, in itself, a step toward healing.

Because if difference is treated as a threat, and not as a signal that deserves further research and curiosity, we may be headed toward a society with nothing but monologues. All of us are broadcasting into bespoke echo chambers, fueled by click-ready outrage, never warming to an actual conviction. We want dialogue not because it’s easy, but precisely because it’s the only way to live together without war, whether on the physical, cultural, or epistemological plane.

The fact that we fear people we don’t know leads us to reject them when we’re afraid of them. And in dismissing them, we become the very force we purport to oppose.

These sorts of things are not always something we can arrange to come across ourselves. But when the door opens, whether it’s a co-working space, a family reunion, or even a coincidence on an airplane trip, it invites you to step into a moment of healing, disorienting truth. Seize it. Step into it. Ask more than you argue. Assume less than you explain. Allow the invisible one to become visible.

And then, with a quieter courage, ask yourself: Are they, too, listening, reaching, and reckoning? And what if the “other” was never other at all, but merely… us, unrecognized?