Pakistan is a country known for its vibrant diversity seen across the numerous cultures nestled within this state. Among the various cultures, it remains a living testament of cultural fusion, forged across centuries of history. Surfing through the coastal belts of Balochistan and Sindh, one might come across one of the most indigenous and high-spirited communities that Pakistan has to offer. The Sheedis, Pakistani Muslims of African descent, are known for their indigenous culture. The Sheedis are a symbol of Pakistan’s pride and resilience, as evident by their endurance of systemic discrimination through numerous generations. Known for having the highest number of Afro-descendants in Asia, the Sheedi population in Pakistan ranges from 50,000 to 1 million, according to the Young Sheedi Welfare Organisation.

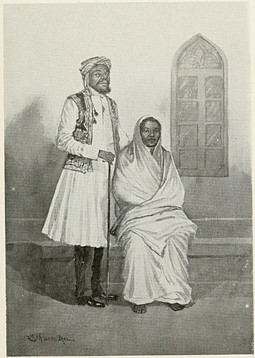

According to Amy Catlin from the University of Chicago, Sheedis first came into the region of South Asia in the 12th century. Known to be the descendants of African slaves brought by the Portuguese, they first reached this area through the sea trade between Africa and the Gulf in the 12th century. However, many others believe that Sheedis were of Arabian descent. Moreover, the time of their arrival in South Asia also faces conflict, where many sources believe that the first sheedis to have reached India (specifically Bharuch port) came around the time of 627-628. It is also widely believed that Sheedis were part of the first Muslim conquest in the subcontinent, originally soldiers named “Zanjis” from Muhammad bin Qasim’s army.

The Sheedi culture is one that is vibrant with respect to its music and dances. As the month of Rajab has begun, so has the weeklong Sheedi Festival at the shrine of Saint Manghopir. Known for its sulphur springs and the decades-old harvested crocodiles by the shrine keepers, the festival of the crocodile includes feeding the reptiles at the shrine, along with performing dances at the beats of the magurnam drum. This practice shows how assimilation has played its role within the sheedi culture, where African values have been integrated with those of South Asian Sufi ones. Moreover, the Sheedi dance and the playing of the mugarman drum can be seen across various shrines in Karachi and Makran. In addition, in order to ward off evil spirits from possessed individuals, the sheedis practice a special type of exorcism, “gwati exorcism.” This exorcism is characterised by a series of days in which animals like goats or chickens are sacrificed, ritualistic dances are performed, and lastly, special meals are prepared. Moreover, in an old newspaper, it is written that the Black Lyari women may be “the most liberated women in Pakistan and have little inhibition to be seen out in the streets.” However, it is to be noted that this might not be the case in today’s Pakistan, where Sheedi women are prey to early marriages, racial discrimination, and colourism.

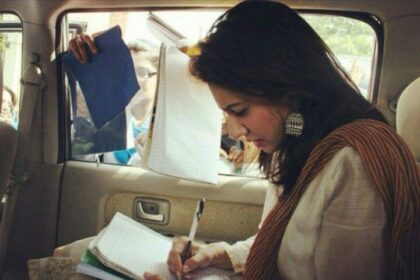

The circumstances of this country have made life harder for the Sheedis, leading to about 85 percent of the Sheedi youth being unemployed or labouring. Not to mention the social and racial discrimination where even the word Sheedi is considered a slur among the masses. Moreover, the Sheedis have experienced limitations to express themselves, as evidenced by the various bans on the celebration of the festival of crocodiles due to security issues, the rising religious orthodox targeting Sheedi practices, and the decades-old discrimination portraying them as “evils, thieves, and unwanted.” They have faced backlash from the mainstream community with respect to political participation as well, which can be seen by the struggles faced by Tanzeela Qambrani. She was the first Sheedi woman MPA for the Sindh Assembly. Due to her political affiliation, Qambrani was removed from her municipal council in Badin by her own party members. Furthermore, the circumstances of Sindh and the Lyari gang wars have further threatened the Sheedi’s right to expression. Interracial marriages for sheedis have become another problem since the colourism, passed down from the colonial era, has influenced the lives of many.

It is high time that the people of Pakistan start embracing each and every community, regardless of their race, caste, religion, creed, or other societal structures. Their merits should be who they are and by appreciating their contributions to the country. These ethnocentric beliefs might be the death of all indigenous cultures and therefore the life and colour of Pakistan. It is time to embrace the Sheedis, as they have embraced Pakistan as their own.