In dusty corners, where files sit untouched and names are reduced to mere codes, the archive becomes less a record of history and more a crime scene of neglect. What we inherit are not neutral facts but curated silences — censored files, forgotten lives, and erased names. A dusty textbook, a redacted name, and an empty history chapter are all pushed to the far back — hidden, forgotten, and not really needed. It seems like a game of push and pull, one that decides who deserves to be remembered and who is forgotten.

Curiosity is vital for humans to evolve, so it is considerably confusing what these “archives” are: fragments of history ripped off from not just textbooks but also documents, snippets borrowed from the public’s conscience warped with a new reality and finally censored stories quickly gotten rid of to preserve public image.

There are two general categories of crime: one that is visible and then the one which goes unnoticed. These archives are victims of the latter — erasure, ignorance. Significant parts of history are being covered up by dirt and grime. Growing up with stories being narrated with pauses and gaps in between each crucial detail, you start to ponder what even is the truth.

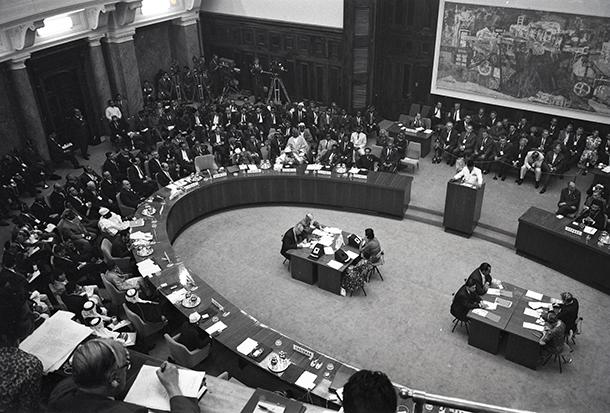

The archive is clipped so what enters a museum, library or textbook isn’t randomly chosen; it is deliberately placed. It is decided whether this narrative is worthy of being catered to. We often mistake memory for neutrality but remembering is political. So for every inclusion, a larger exclusion is witnessed.

The main idea becomes deliverance — not what is remembered but rather how it is remembered: heroes without their failures, revolutions without their casualties. It was never up to us who gets remembered as a “freedom fighter” and who is dismissed as a “threat” or “traitor”. These decisions are made in large backrooms, welcoming power through caste, class, gender and nationalism. The archives become more of a mirror than the truth.

Across decades the archives we inherited were made deliberate — missing people, censored reports and displaced truths are all kept locked away in a dark, grimy corner. Years-old partition documents lay safe in vaults hidden away from the public eye in both Pakistan and India, as if opening them would re-emerge centuries-old raw wounds, often glossing over the scale of suffering and bloodbaths witnessed, instead rejoicing with accounts of separation.

In a country run by patriarchy, the lesser, softer characters suffer, so it was never questioned how, in schoolbooks, women are displayed as simply wives of emperors or, more commonly, their “kaneez”, part of their harem of several others — their rebellions, contributions, and writings are scrubbed from pages. Our official narrative could never be home to dissenting freedom fighters, rural communities being written over with potential hymns of colonisers, their struggles and ways of life being ignored.

These acts of force are known as tampering; in more forensic terms, it could end in tampering with fingerprints at a crime scene, a blacked-out name, or a redacted file. Where truth ought to be clear, we have obscure, mismatched documents with messed up timelines — vital information is hidden away. In human terms, it’s erased. Thus the silence we inherited was not an option but was made mandatory.

The only time it ever slipped out was in the kitchen when rolling pins collided on countertops, flipping of roti’s was being brought out, and a distracted murmur, “when we were younger…”, immediately clamped their mouths shut once having realised what slipped through. They preserve what wasn’t written, earning the title of the matriarchal memory bank, sliding short snippets of forgotten history in bedtime stories and referencing certain events in carefully crafted lullabies. History was kneaded into the dough, tangled with the frayed edges of dupattas.

“The stories we tell, the songs we sing, or the wealth of immaterial resources are all that we can count on.” ― Saidiya Hartman

So if the official archive is the crime scene, then the matriarchal memory is our secret reserve.

Memory can never be redacted fully; it finds ways to bleed out into public reserves, finding its rightful home in the margins of dates, slipping through every eerie attempt at being hidden away for what is the truth if not haunting? And this generation is not looking away; instead, it is creating its own archive — making space for all the names that never made it into museums or textbooks, to speak of women not as shadows but as notable characters.

Today memory has new weapons. It lives in zines and newsletters — resting in Substack essays and Instagram captions. In quiet poems written by carefree hands sent over to student-run magazines. Living in the questions boys raise about the idols they were told to worship and in the silence girls witness from their mothers and grandmothers.

Permission was never needed to preserve, and if they won’t include our stories, we’ll simply rewrite the margin to fit. With all its blood, sweat and tears for the truth, it never deserved to be forgotten; it needed to be seen.