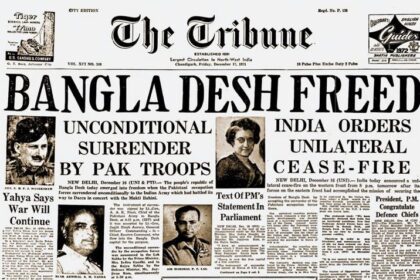

Poetry is an exaggerated reflection of reality; when reality is bleak, poetry is bound to exude despondency. The rise of the sadboy shayar on social media is not an isolated development — it is a reflection of the society we live in. There is widespread uncertainty, suffocation, and a woeful lack of opportunities for young people. Young degree holders knock on countless doors until their hair starts to grey, yet they struggle to land good jobs. Even worse is the issue of lovelorn boys. Love is famous for delivering a high-voltage jolt at a formative age, but when society spurns love — when it is seen as a devilish taboo — it gets much more complicated. So, while the sadboy reels on Instagram might appear performative and cringeworthy, they undeniably resonate with the lived reality of young people.

The music and poetry produced in the subcontinent have a particularly strong flavour of despair and jilted love. Compared to Western poetry and art, South Asian expression contains a much deeper layer of love — especially unrequited love. The bigwigs of poetry, i.e., Ghalib, Faiz, and Jaun, all carry a strong tinge of lost love and mehboob ki berukhi. Why is the extreme form of jilted love and its subsequent pain, as manifested by the likes of Jaun, so popular among young men? Sigmund Freud says that feelings which do not reach fruition never die — they get buried deep inside us and later manifest in much uglier forms. A society that suppresses emotions, that treats the expression of love as deviant and immoral; a society that thrives on suffocation and hypocrisy at its very root — is bound to produce a wave of sad young men.

The widespread use of Zia Mohyeddin’s recitation of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s verses, layered with melancholic music in the background, is part of the same cultural expression. It’s a form of complaint, a means of escape into the world of awe-inspiring poetry. It is also a testament to the fact that no amount of grating Bollywood music can compete with the artistic genius and sophistication of these preeminent poets. No amount of budget or large studio can replicate the kind of musicality that abounds in the couplets of these literary masters. The sad boy of today’s generation finds comfort in the emotional depth of this poetry. He is living proof of the timeless nature of the poet incarnate.

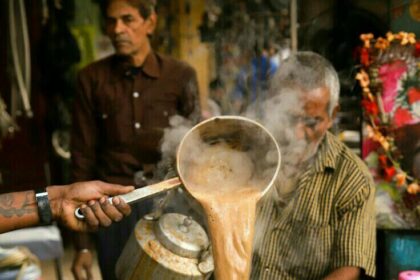

However, some of the sadboy reels are more about the performance of masculinity. Sadness is associated with coolness and masculine depth. Shaped by a history of tragic heroes in films and plays, the sadboy mirrors the protagonists he grew up seeing on screen. A happy man is less cool. This melancholy becomes, in part, an appeal to the motherly instincts of the opposite gender. The visuals of smoke billowing from a cigarette, accompanied by a classic qawwali or poem, are part of the performance. It casts the sadboy as someone artistic — someone with good taste in poetry. While women try to wrap their heads around the daily struggles of surviving in a patriarchal society, the sadboy is nonchalant. He is beyond the mundane. He exists only as an emblem of poetry, art, and aesthetics. The performance of masculinity is most certainly part of the sadboy package.

Young men struggle to shed tears or express vulnerable emotions in real life. Yet, they share deeply moving poetry and reveal a softer side on social media. This paradox can only be explained through the lens of gendered imagery. Crying and shedding tears are considered feminine acts, while sharing melancholic poetry is seen as glum masculinity. Sadness is acceptable — crying is not. Men who are sad are seen as manly and heroic; those who cry are considered weak and feminine. The burning stub of a cigarette and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s voice in the background are now features of masculinity. Perhaps young men have taken Judith Butler’s famous quote — that gender is performative — to heart. Masculinity, for them, is a performance, and Instagram is the stage upon which it is played. The masculine man doesn’t enjoy pop music; he enjoys classical, sentimental poetry — or at least, that’s what he pretends on Instagram.

In a nutshell, it is easy to dismiss the tale of the sadboy shayar as cringeworthy and performative. However, the abysmal socio-economic realities cannot be ignored. These realities deeply impact lives — particularly those of young men — who carry the heavy burden of becoming financially independent and emotionally resilient. Maybe we should let them be. One cannot stay too angry at the sight of good poetry. It’s still better than virtue signalling and pointless political gibberish hurled back and forth. No one has ever been harmed by a few innocent couplets of Ghalib or Faiz (though Faiz’s revolutionary poetry might raise a protest). So let us be a little less harsh on the “cringe” aesthetic — and the associated rise of the sadboy poet.