A society’s true values emerge in the way it protects—or fails to protect—the powerless. When justice systems fail to protect the vulnerable, they often perpetuate cycles of oppression that stretch across generations. In places where gender inequality is already deeply entrenched, the conscious overlook of violent oppression can bear grave social outcomes. It can lead to the invalidation and ridicule of victims by their community. Pakistan’s handling of sexual violence over the decades offers a striking example of how legal systems, societal attitudes, and institutionalized biases can give birth to a system that blames the victims rather than holding the perpetrators accountable.

Pakistan is a country dictated by clergy Islam. Here, importance is given to the values preached by religious clerics rather than the facts upheld by the religious text. As a result, many of these teachings arise from individual perspectives and traditional norms rather than Islamic literature.

In Islam, Hirabah refers to crimes that instill fear or cause harm. It is considered a major sin and a capital crime in the jurisprudence. The Qur’an prescribes four punishments for Hirabah: execution, crucifixion, amputation of hand and foot, and banishment. Sexual assault is a crime of Hirabah. The religion recognizes that any act committed under coercion absolves the victim of blame. Even Shirk, or renouncing one’s faith under duress, is not punishable in Islam, as the compulsion removes personal agency. Similarly, rape is an aggressive act of domination where the victim is forced into submission through physical and psychological threats. Despite this clear framework in the Fiqh, the state of Pakistan has systematically oppressed and silenced the victims of this heinous crime through deliberate and flawed legislation.

After gaining independence, Pakistan adopted the British Penal Code of 1860, which defined rape as non-consensual intercourse but placed the evidentiary burden on the victim. The victim had to prove non-consent, often with a display of physical injuries. Since there were limited forensic resources and the courts were entrenched in patriarchal biases, victims were routinely disbelieved and shamed. Despite having three constitutional revisions—in 1956, 1962, and 1973—the penal code of Pakistan, with all its inefficiencies, remained the same. Women were systematically bullied for demanding justice. The reporting of rape was discouraged through difficult trials, humiliating medico-legal procedures, and a male-dominated judicial machinery.

The situation worsened during Zia-ul-Haq’s regime in 1979, when the Hudood Ordinance was introduced to align Pakistan’s legal system with the Islamic Shariah. In these ordinances, an ambiguity was intentionally created between Zina and rape, failing to classify rape as a crime. Since Islam considers Zina a major offense with Hadd punishment, categorizing rape with it implied that there was a similarity between the two, causing unnecessary guilt about rape. The Hadd or Tazir punishment for Zina was therefore given to the victims of rape. Pregnancy out of wedlock was punishable as Zina, even in cases of rape. Evidentiary conditions, like the provision of four male eyewitnesses of the act, were almost impossible to deliver, making the situation even more unfavorable for victims. When the victims could not provide four eyewitnesses of sound character who had witnessed the crime being committed against them, they would be charged with Qazf, or false accusations. The situation was absurd: four men of good character witnessed a crime, the crime was still committed, and they still emerged as men of good character.

The infamous Blind Zainab case epitomized this era’s cruelty, showing how victims of rape were systematically silenced, invalidated, and punished by the state. These laws not only denied justice but also reshaped societal attitudes, conditioning generations to equate rape with moral failing and blame survivors for their suffering.

It was not until 2006, with the passage of the Protection of Women Act, that rape was criminalized and legally distinguished from Zina. Rape was redefined, and seven defining conditions were set: if it was committed against someone’s will, without someone’s consent, with someone’s consent but under the fear of death or hurt, consent obtained under intoxication, if the person is unable to communicate consent, and if the person believes they are married to the perpetrator but they are not.

Rape thus became punishable by death or imprisonment. However, the legacy of systemic injustice persisted. Reports from Amnesty International in 1998 and Human Rights Watch in the early 2000s highlighted that by 2003, up to 80% of women in Pakistani prisons were incarcerated due to accusations of Zina, often following instances of sexual violence. The HRCP concluded that the country-wide incidence of rape, including unreported cases, was in 1997 “at least eight women … criminally raped every 24 hours, more than two of them by gangs, and more than five of them were minors.” (Amnesty Report)

According to a recent study released by the Biological and Clinical Research Journal, 11 cases of sexual assault are reported every 24 hours in Pakistan. Such are the numbers. Yet, the conviction rate of rape remains below 1%.

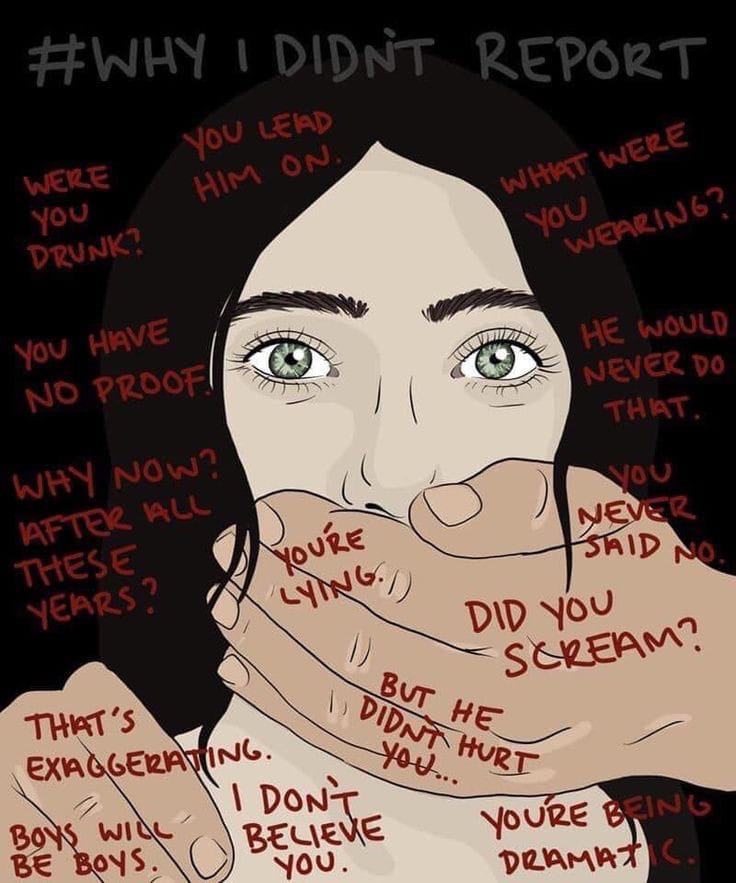

The institutional injustice inflicted on women for over sixty years was bound to bear social implications. By intentionally blurring the lines between rape and Zina, the state cultivated the mindset of an entire generation to believe that both these terms were interchangeable. This not only undermined justice but ingrained the societal belief that the victim of rape was somehow complicit and perhaps “asking for it.” By the deliberate misuse of Quranic conditions meant to prove adultery, applied instead to cases of sexual assault, the state played monopoly with humanity and religion both.

A nation of people does not wake up one day and decide they want to disregard victims of such a pervasive crime. It is done intentionally and institutionally to propagate oppression, fear, and distrust in the masses. According to UNFPA, 56% of the women who have experienced any kind of physical or sexual violence have not sought help or talked with anyone about it.

Through systemic victim-blaming, shaming, invalidation, and ridicule, the state of Pakistan has achieved a perfect dystopia. A society that prides itself on the honor of its women must confront the hypocrisy of its actions. Without justice, dignity, and accountability, that pride is nothing more than an empty façade. The shame lies not with the victims but squarely with the state, its enablers, and patriarchy.