Winters in Pakistan have undoubtedly become notorious for the wedding season they bring—a nolens volens of sorts. As ceremonies follow through the interplay of colours, one problem in particular remains as critical as when it first began; only today it is glamorised in a different lens. This is for the dowry apologists and for the benefit of the residents of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the Kaafirs.

Recently, I had the not-so-unusual opportunity to attend a close friend’s wedding. Amidst the many fragments of chef de partie-like critiques (which deserve their very own debate), family politics, and the godlike ornament that is public opinion, I couldn’t help but nitpick a casual comment, executed as airily as the next stray handshake: “We’re not taking any dowry, except which you’d give with your own love.” To the more seasoned readers, this remark isn’t a first. One way or another, we’ve seen this materialise in everyday moments: the silent acknowledgment of a woman as a separate entity from her family, the mercenary nature of her otherwise God-endowed duty of companionship, and the consequences this has for the next woman in her bloodline.

What even is love? How credible does it remain to be held equivalent to one’s entire home decor? Is there such a thing as too much dowry? And what percentage of one’s wealth needs to be depleted in order to qualify as loving enough? When I posed these questions to a friend, he left a Sahir Ludhianvi couplet that I must share.

Ik shahanshāh ne daulat kā sahārā le kar

Ham ġharīboñ kī mohabbat kā udāyā hai mazāq

(A king, relying on his wealth,

has mocked the love of us poor souls)

Dowry culture in Pakistan is a multifaceted issue, far too complex to be reduced to something as simple as tradition. It is a foul intertwinement of socioeconomic expectations, patriarchal legacies, and the convenient misinterpretation of religion that Pakistan is known for. Despite its deep entrenchment in the cultural fabric of our nation, it is crucial to dissect it both from a feminist perspective and a religious lens (for the faint of heart unable to digest un-Islamic narratives akin to Aurat Raj). This system cannot be entirely understood without recognizing its historical underpinnings, which, you name it, originate from Hindu traditions predating the advent of Islam in the subcontinent. Dowry, referred to as dahej and conveniently renamed jahez to allow for chauvinist cultural appropriation, is an amalgamation of outdated rituals and antiquated psyches. This very fact requires nuance, because in a nation ridden with hypocrisy—where mehr is a second thought arrangement postponed indefinitely because the husband’s money is the bride’s money, of course, but baraats are mandatory to ensure the bride’s family spends just as much if not more—this is a slap in the faces of the self-righteous and a cultural relic of the pre-Islamic practices they so flamboyantly reject.

From a feminist lens, dowry culture perpetuates the already widening gender inequality and reinforces patriarchal norms. The very expectation that a bride’s family shower extravagant gifts (which constitute anything between an IKEA showroom and a real estate holding) in order to secure her “good standing” in her husband’s household is loathsome. It stems from the ingrained belief that a woman only truly belongs in her husband’s house, and nowhere else, which is ironic because the one place the entire social fabric holds consensus on is the same where she must bribe actively to be worthy of respect. This not only exacerbates the gendered economic gap but also reduces a woman’s merit to the financial value she adds to her new household. Quite the business deal, and yet, a financially independent woman is just as ferociously hated. As if she encroached upon another’s ambitions to be able to not rely on others for her survival.

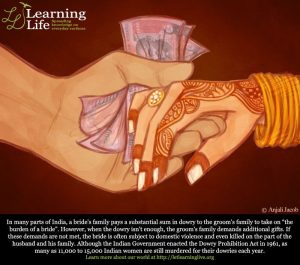

The darker side of the dowry system is the inherent contribution it makes towards systemic violence against women. Dowry-related abuse, from emotional coercion to physical harm, is not uncommon in Pakistan. This commodification of women is a reflection of the internalised misogyny that both allows and amplifies the presence of this practice. Reinforcing traditional gender roles, framing women as dependents whose primary value lies in a good match, and curtailing their very humanity in order to prioritise marriage are things that seem like another sociology excerpt. But for the women in Pakistan, they are a time bomb, constantly ticking.

It is important to realise that not only is dowry a deeply-ingrained social issue, but an equally stubborn one, and addressing it requires a long-term approach that combines both cultural sensitivity with legal jurisdiction. Instead of announcing TikTok-worthy projects like mass weddings and dowry support, the government needs to focus on reevaluating both its critical capabilities and the people whose representation it has repeatedly hijacked. Beyond this, public discourse plays a crucial role. It is high time our sorry entertainment industry began directing storylines outside of the hypernormalisation of woman-hating, because woman-hating kills.

The people of Pakistan should make a decision after all: do they wish to be labelled as the devout Muslims they imagine themselves to be, or do they cede to the secular culture Pakistan was meant to adopt? Neither provides space for patriarchy to persist, and both require amendment in the community and self. It is time women cease being pressured into aimless unions in the name of social conformity and begin rejecting these dowry-demanding men for who they are: strategic parasites. No marriage is vital enough to leave this mark of gendered larceny. Only when we overcome the taboo surrounding male rejection can we reimagine our place in society that is solely ours. Not the name that comes after.