Media Censorship in Pakistan: Censorship in Pakistan is often associated with PEMRA notices, social media breakdowns, the mysterious disappearances of journalists or the sudden banning of television transmissions or news channels. But these incidents are not new; they date back to the authoritarian history of Pakistan, namely the so-called “Martial Law eras”, when the government introduced the whole concept and art of silencing dissent under the badge of national integrity, patriotism and religion.

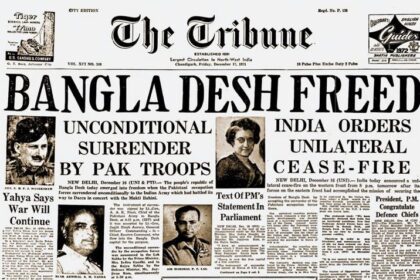

Although history offers numerous examples of censorship dating back to pre-martial law regimes, the phenomenon gained prominence with the first martial law regime under General Ayub Khan (1958-1969). During this regime, the state centralised control over the process, establishing multiple institutions, such as the Press and Public Ordinance, to monitor and regulate journalism in all forms. Newspapers that questioned the government policies faced censorship, blacklisting, or outright bans. The same model was faithfully adopted by other martial law leaders like General Yahaya Khan, General Zia-ul-Haq and General Pervez Musharraf.

It was under General Zia’s regime that this whole concept of censorship evolved from political control to moralistic or theocratic policies. General Zia used religion as a weapon and introduced harsh blasphemy laws. Journalists were flogged publicly, publications were widely banned, and the concept of self-censorship arose among the journalists of that time. The trauma of that era still haunts and continues to shape the media landscape, instilling fear and hesitation in voices questioning the state regime. His censorship reshaped popular culture, making PTV dramas preach conservative values while dissent and satire disappeared from media.

In Pakistan, the concepts of ‘national interest’ and’religious sensitivities’ have long served as a cover for censorship. This censorship still exists, somehow in a different way than before but driven by the same old fear of dissent. Since 2020, TikTok has been banned multiple times in Pakistan for “immoral” content. In 2023, internet services were shut down during protests to curb mobilisation. Journalists like Imran Riaz Khan disappeared temporarily after criticising the establishment online.

Talking about the digital age, the procedures may have changed, and the tools may have been replaced but the intentions are still the same. Internet blackouts during political protests, the misuse of cybercrime laws against critics, or the tactics of surveillance under the curtains suggest the absence of free expression for the citizens of Pakistan. Social media, which once provided a platform for unfiltered speech, is now at risk, as content removals and account suspensions have become quite common these days.

Yet, as the saying goes, “Every dark cloud has a silver lining.”, In the midst of this chaos, independent journalists form a resilient resistance by continuing to speak the truth, challenging state narratives, risking their lives, and presenting themselves as beacons of light and hope in an otherwise stifled media environment.

To truly move forward, Pakistan must confront the whole situation in a way that the state must get rid of this flawed idea that dissent or criticism is unpatriotic or a red flag to the national integration and that religion can be used to delegitimise opposing viewpoints. It should accept the fact that true democracy lies in disagreement, debate, criticism and opinions and not by enforced silence. If these ideas aren’t shifted in policy and mindset, Pakistan risks slipping further into authoritarianism, and it cannot claim to be a democratic society. For Pakistan to mature as a democracy, free expression cannot remain a negotiable right — it must become the nation’s loudest voice.