A love letter turned cultural critique exploring the deteriorating state of Lahore.

Eyes sparkling with the possibility of the impossible, hands tingling with anticipation and minds sizzling with ideas that couldn’t be contained, two teenage girls stood hesitant at the threshold. “Remember, Faiz and Manto used to frequent this cafe—there’s probably a membership required”, whispered one of them, but curiosity was stronger than embarrassment, so they rushed inside. As the door shut behind them, the outer world was long forgotten. There was a haunting air of poetic immortality that clung thickly to the surface of the walls and each piece of furniture. An overpowering sense of reverence took over, turning each mundane thing into a historic artefact.

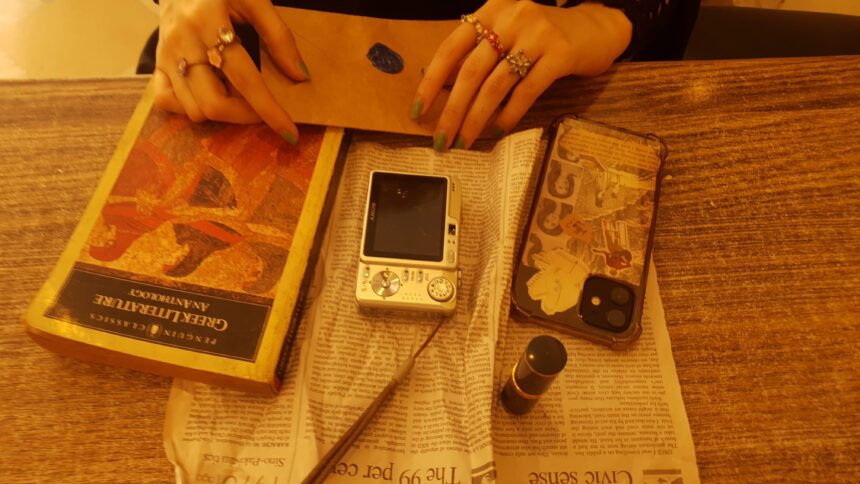

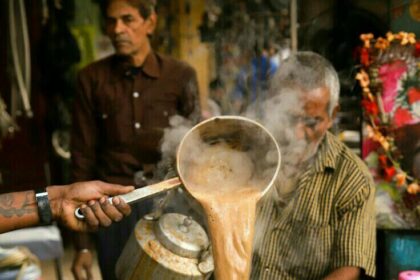

A man, clad in starched brown button-down and slacks, came over to the table, asking the girls if they wanted coffee or tea, which happened to be the only thing on the menu—a perfect place for spiritual enlightenment rather than bodily nourishment. The walls had portraits of poets, artists, revolutionaries, musicians, writers and dreamers who had turned this corner into a sanctuary. Shelves with worn-out books that made you wonder the endless probable identities of readers before you, the ghost of whom was painfully existent still. The table in the far-left corner was occupied by a group of grey-haired men peppered with some university students in adorned blazers. A sentence or a verse in sweet, sophisticated Urdu (spoken in a tone long lost) from their table would find its way to the girls who would become one with the tender, intellectually perpetual cloud of enquiry.

This was the story of me and my best friend going to Pak Teahouse for the first time. There’s a deceptive, hopeful feeling evoked by this tale that ends in tragedy. When we recently revisited this same cafe—it was selling biryani, pizza, pasta—a hubbub of families, boys with highlights in their hair and vapes in their hand were cursing and guffawing, every known stench was oppressively pushing down on the people, these antique tables had ketchup seeping down their crevices as the disapprovingly mournful eyes of the legendary portraits looked down helplessly. Was this the ultimate reality of Lahore?

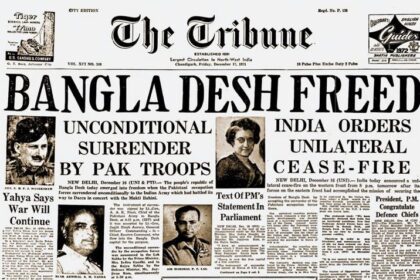

The city of gardens is chopping down trees to build skyscrapers that house the capitalistic den, which we call “modern culture”. Culture? Was it culture when Miss C.M. allowed the chopping down of a 400-year-old tree outside The Shalimar Gardens? Was it culture when parks went from being tranquil hubs of introspection and artistic self-exploration to the frolicking grounds of junkies and TikTokers?

The city of gardens is chopping down trees to build skyscrapers that house the capitalistic den, which we call “modern culture”. Culture? Was it culture when Miss C.M. allowed the chopping down of a 400-year-old tree outside The Shalimar Gardens? Was it culture when parks went from being tranquil hubs of introspection and artistic self-exploration to the frolicking grounds of junkies and TikTokers?

The black and white footage of Lahore from the past is more vibrant than the stories of the multitudinous social media influencers who frequent the same commercially affluent restaurant chains and shopping malls. Maybe there is a certain cynicism that shapes my views, but it stems from an all-encompassing frustration of being born today. My Literature teacher with her polaroids from a time when the likes of Zia Mohyeddin would make a name for themselves and Pakistan as far as Hollywood—just to successfully bring William Shakespeare on the stage in Lahore, record stores with vinyls of obscure bands, hand weaved miscellaneous crafted by school girls being displayed for the public, the organic humanity of exploring the exuberant bazaars for the perfect pair of khusas.

Maybe the fault didn’t lie within the city so badly wounded, but amidst the indolence of this generation, which chooses to go to the Dolmen Mall instead of a poetry reading or a book club. There are these daring individuals who continually create opportunities, which glimmer sparingly in this ocean of consumerist idealism, but a lack of interest and engagement forces them into obscurity. This weekend, for example, I visited a bookstore in Gulberg that was hosting a poetry circle. There was an elaborately curated collection of books, colourful rickety chairs, cushions with embroidered poems, hopeful spaciousness that bore the blow of inadequacy, as only a handful of individuals showed up. This mutilation of sorts finds its genesis in a certain feeling of victimhood inspiring immobility. The slums in New York City turned into gardens as the rebels threw seed bombs in the places the racist government deliberately wanted to cultivate repugnance within. Imagine how gardening became mutiny, and those who wanted nature to sprout its all-nurturing arm were imprisoned! What Lahoris ought to do is support those who are trying rather than bemoan a fate that will only worsen if neglected.