The 2025 Global Liveability Index, updated by The Economist, has cited Karachi amongst the five least livable cities in the world.

This is a glaring label, but who placed it there? And who does it claim to label?

The ranking reflects a certain level of ground-based crises in Karachi. Still, it is also important to note that it represents a West-centred, imperial framework that is biased, in that its motive is to help white-collar professionals relocate to ideal spots, as clarified by The Economist.

The methodology used to devise the list is systematically in favour of rich, Western cities, which third-world countries simply cannot be expected to compete with—given the cards they have been dealt. Moreover, some of the indicators used are questionable, as the index ranks things like ‘climate and geography,’ as if such structures are alterable.

There is also a huge emphasis on the quantity and quality of lifestyle utilities present in the cities in comparison to more basic metrics such as education. Education comprises a mere 10% of the total index, whereas the more value-adding metrics, such as sports, art, and quality of food services, comprise a staggering 25%. This further places developing cities on the back burner as they struggle to solidify their basic pillars of being, which in many cases were deteriorated by years of exploitation and corruption.

All in all, the metrics used are biased towards cities that have a structural advantage of greater wealth accumulation, largely as a result of the world order resulting from the colonial and imperial expansion of the 20th century. Daren Acemoglu’s book “Why Nations Fail” represents this idea well, as it describes that countries that are considered successful or part of the developed “first world” are simply those that have managed to build first-class institutions based on the extraction of resources from the developing “third world.”

Hence, it is not a fair judgement to simply label struggling cities like Dhaka, Damascus, Karachi, and countless others that suffered the fate of colonial extraction as the “least livable.”

The context underlying why they are unlivable and what factors have led to this dismal position are important so as not to make the labels a blame game where some cities are dismissed as unworthy or just not good enough compared to other cities, as if those cities naturally have an unfortunate place.

Nothing about how these cities came to be “unlivable” is natural. The structural factors leading to their current condition in an undeniable way hold those very Western governments and institutions accountable—the ones that claim to be the vanguards of civilisation and decide what it means for a city to be livable.

Having understood that, it is also important to acknowledge the factors contributing to Karachi’s dysfunction that are internal and addressable and not simply attributed to external, Western action.

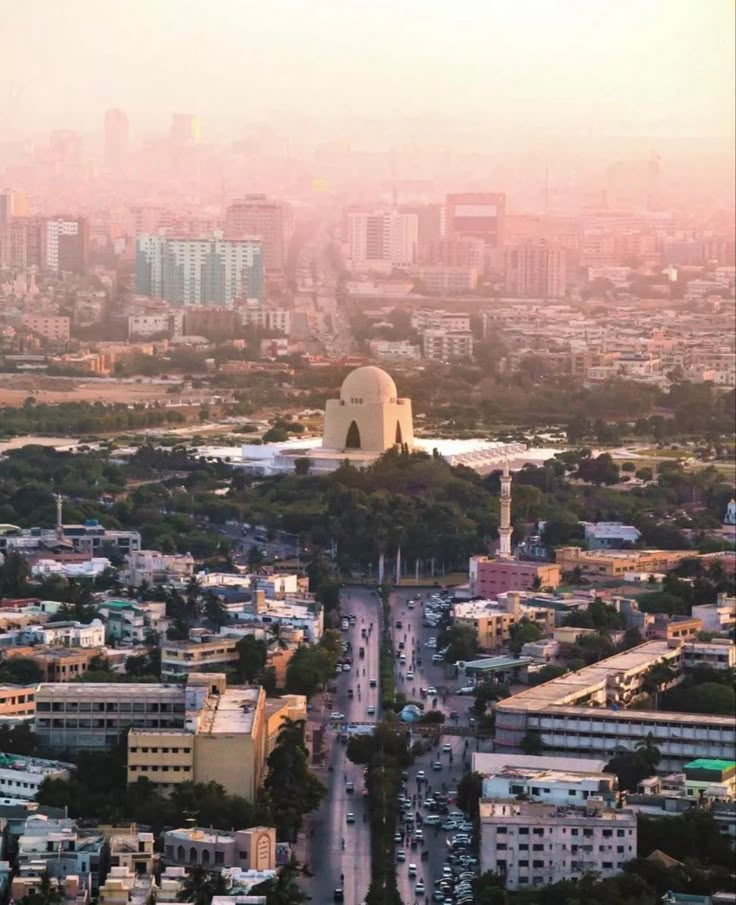

The infrastructure in the city is the most seminal representation of negligent policy and the dysfunction the city faces as a whole. It is a miracle to even see areas in Karachi that do not look rundown and without parts of rubble or heaps of rubbish—it has almost seeped into the culture of our city—and the parts of the city that do not have these scenes are only to be seen in private housing societies, the likes of which are so elusive that you’d have to try hard to find them even within these exclusive areas.

Karachi is an abandoned city, as neither the central nor the provincial government is likely to gain much out of its voting base come election time. An article in The Express Tribune quotes Atiq Mir as he describes, “Karachiites pay heavy taxes, and not even 10% of these funds are allocated to the city’s roads, infrastructure, and sewage system. Street crime increases while various mafias, such as those controlling water tankers, parking lots, and encroachments, monopolise services.”

One of Karachi’s biggest problems is its invisible but very glaring divisions along the lines of class, ethnicity, religion, and municipalities. The elite occupy private housing schemes and towns such as DHA and Bahria Town, while the poor live in slums and are cornered in more abandoned areas such as Karachi East. Even basic access to clean water or garbage disposal depends on which “Karachi” one lives in, making it seem less like a city unit and instead a patchwork of different municipalities.

In lieu of the above, I believe that it is important to be extremely careful with using terms like “most” and “least livable” because these do not leave room for considering things like improvements in policy and the lived realities of so many people. An index devised by a firm based in London cannot and should not speak for the real life that so many are learning to live—and love—in their city.

In response to the list, Karachi’s mayor, Murtaza Wahab, commented that it was dismissive of Karachi’s “vibrancy and resilience.” Whether this was for PR or genuine is debatable, but what’s important is the dismissal of the label. The people of Karachi have found a way to survive, live, and thrive despite their systems failing them. There are street vendors, artists, government workers, youth, etc., who would choose to defend and stick to their loyalty for the city despite its dysfunction. Labelling a city unlivable deems it inherently unworthy of even trying to improve it, which can reinforce the political and social abandonment Karachi has already been facing for far too long.

It is irksome to think that a list published by a few reporters and analysts based in an office of a city that is part of a former exploitative empire, working on a report meant to be for white-collar workers—so they can choose their preferred destinations of travel or relocation—can dismiss the efforts, struggles, improvements, and most importantly, the complex and rich lives of so many people living in a city they would repeatedly choose as their home to live in.

We acknowledge that Karachi is struggling, but we certainly do not accept the label of the city being “unlivable,” because it strips the city of the right to demand better and the agency to improve, as it deems it inherently unworthy to improve or to live in.