Pakistan is one of those countries where justice is served partially—only to those who either have enough power to influence the system and turn the tables in their favour easily or to those who exhaust years of their lives running to and from courts in pursuit of justice. The country’s rank on the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index is enough to explain the state of Pakistan’s justice system, standing at 129th out of 142 countries worldwide.

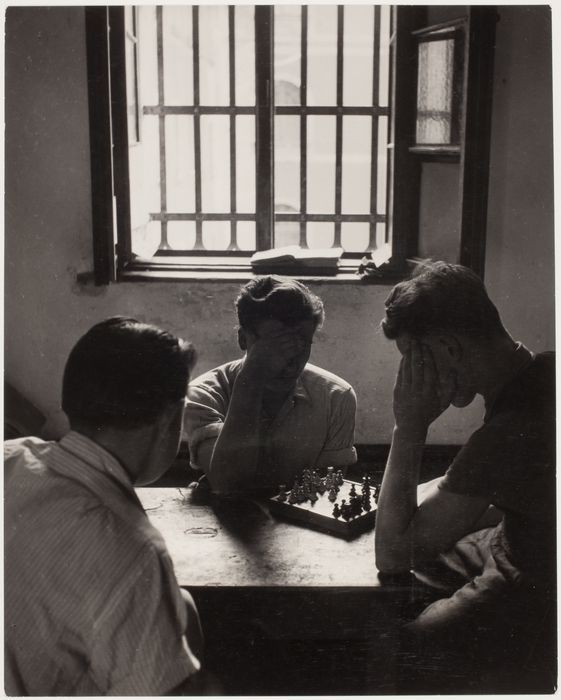

Another disturbing factor is the illegal arrest and detention of innocent individuals. The criminal justice system takes decades to prove their innocence, and often, they are exonerated only after their demise in prison. This dismal state of affairs further extends to young offenders, known as juveniles, who face even worse circumstances within Pakistan’s legal system.

Juvenile Justice System of Pakistan: An Ideal Facade

A juvenile delinquent is a young person who has committed a crime and is below the ordinary age for criminal prosecution. The age of juvenile offenders varies across countries. In Pakistan, juveniles are dealt with under the juvenile justice system. According to Section 2(b) of Pakistan’s Juvenile Justice System Act, 2018, a child is defined as a person under the age of eighteen years. Furthermore, Section 2(h) defines a juvenile as a child offender who should be dealt with differently from adult criminals. This law also mandates that juveniles must be kept in separate jails and that the legal procedures for dealing with them should differ from those of the adult criminal justice system.

Moreover, the Juvenile Justice System must act efficiently to deliver justice to children; this includes their immediate acquittal in cases of innocence or illegal detention. The system is intended to realise and protect child rights in Pakistan, and if viewed from an idealistic lens—without scrutiny—it appears to serve its purpose. However, the reality is quite the opposite. It demands in-depth inspection and urgent systemic reform to protect Pakistan’s children from the wrath of a corrupt, inefficient, and sluggish legal system. It would not be wrong to call the juvenile justice system a mere facade designed to show the world how concerned the state is for its children.

A Legal Death Trap

There are deep-rooted flaws in the Juvenile Justice System Act, 2018. Firstly, it has failed to amend the age of criminal responsibility as defined by Sections 82 and 83 of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), a derivative of its colonial predecessor, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860. Section 82 initially defined the age of criminal responsibility as below twelve years but was later amended to fourteen—still lower than the age set by the JJSA 2018. Moreover, Section 83 deals with determining whether a child between the ages of seven and twelve can understand the nature and consequences of their delinquent conduct. Although amended in 2016 to extend further protection to child delinquents, the age range specified remains between twelve and fourteen years. Thus, these amendments are effectively a lost cause due to the contradiction between the PPC and JJSA age definitions.

Secondly, the Act has failed to institutionalise the Juvenile Justice System in its true spirit. There is still little to no difference in the treatment of adult and juvenile offenders by courts and prisons. Shockingly, there were only two functional borstals (juvenile jails) in all of Pakistan—both in Punjab: one in Faisalabad and one in Bahawalpur. However, the Borstal Institution and Juvenile Jail of Faisalabad have since been shut down, leaving just one operational facility. Sindh has only one functional remand home for juveniles, established eighty-eight years ago in 1937.

According to a 2023 report by Justice Project Pakistan, only about thirty-one per cent of juvenile delinquents are housed in reformatory centres, while the remainder—including innocent detainees—are kept in adult prisons. This grim reality sharply contrasts with the state’s obligation to establish separate remand homes, reform schools, courts, rehabilitation centres, and training institutions for juveniles.

The duration of sentences for juveniles is also supposed to differ from those for adult convicts. The Juvenile Justice System is meant to ensure that child rights are protected during trials and that children are treated fairly by courts. However, this is not the case in Pakistan. Instead of being reformed, rehabilitated, and reintegrated into society, juveniles face an increased likelihood of becoming habitual criminals due to unnecessary delays in trial and their incarceration alongside adult offenders.

Official statistics reveal that there are approximately two thousand juvenile offenders in Pakistani jails, about ninety per cent of whom are awaiting trial—let alone a fair one. Lastly, young offenders are subject to various forms of abuse, including sexual exploitation by adult inmates, while the law fails to protect them. This further increases the chances that they will fall back into crime after their release.

In essence, Pakistan’s Juvenile Justice System exists only in letter, not in spirit, while the state continues to ignore the deplorable condition of juvenile prisoners.