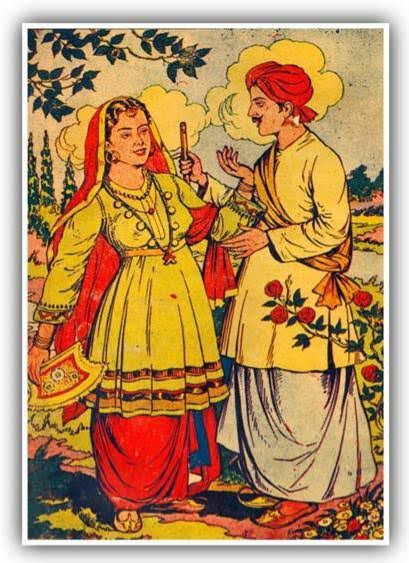

In the villages of Punjab, Heer wasn’t read. She was remembered. Her story lived in the mehfils, echoed from the mouths of old men under peepal trees, and spilt from the dhol of the fakir walking barefoot down dusty roads.

She wasn’t something to be adapted. She was something to be carried.

But today, you can hear Heer on Spotify. You can watch Ranjha cry in slow motion on Netflix as you sip on a chilled Coke while listening to a Coke Studio fusion of Waris Shah‘s verses. Somewhere along the way, Heer-Ranjha became content.

Punjabi folklore doesn’t belong to the soil anymore. It belongs to platforms.

The Disappearance of the Soil

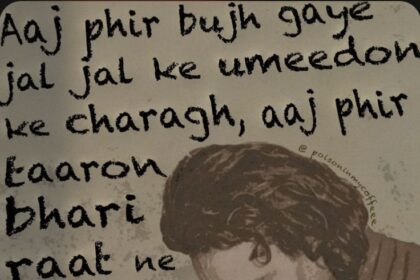

When the world listens to our stories, they don’t hear the language our elders spoke. They don’t taste the dust, the grief, or the rhythm of fields soaked in barsaat. They hear versions — polished, studio-lit, flattened into categories like “folk pop” or “Sufi chill”.

Who Sings for the Land Now?

Not the landless labourer who once hummed Mirza-Sahiban while harvesting wheat. Not the grandmother whose lullabies carried the soul of Sassi. They are being replaced by streaming algorithms and actors who don’t even speak Punjabifluently.

The mitti that gave birth to these stories is being left behind — unseen, unheard.

Folklore Is Not Aesthetic

These stories were not born to be hashtags. Heer-Ranjha wasn’t meant to be aestheticised for playlists or repackaged with EDM drops. It was pain, rebellion, class resistance, and gender defiance. It was about a girl who said no to the system and a boy who gave up privilege for love.

But now, Heer wears a designer kurti. Ranjha looks like a shampoo commercial. The dhol is replaced with synthesisers. And Waris Shah? He’s turned into a captain.

No one asks what these stories meant. They just ask how many views they’ll get.

The Theft No One Sees

This isn’t just modernisation. It’s a quiet theft.

The storytellers of Punjab – rural poets, shrine singers, and village women – never got to trademark their heritage. Their versions were never recorded. Now, their children listen to their own culture with subtitles. They ask, “Did you hear the new Heer song on Coke Studio?” without realising that what they’re hearing is not new – it’s displaced.

When our own people become strangers to their own stories, it means that something is deeply wrong.

What Can’t Be Bought

But not all is lost.

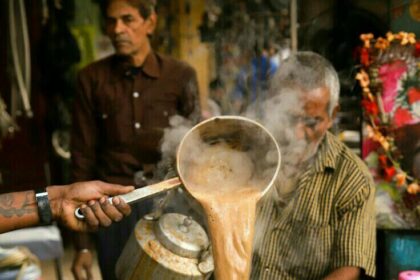

Go to any dargah in Punjab. Sit quietly. Someone will sing. The dhol will beat. A child will lean forward. An elder will close their eyes. And Heer will rise — not from a playlist, but from a place that no microphone can reach.

Because some things don’t belong on platforms. They belong in people.

And maybe that’s the real answer to who owns Punjabi folklore.

Anyone who remembers.