The idea of Nepal transitioning from a period-long autocratic rule to a federal system has surprised many over the decades. Nepal was well known for the absolute monarchy run under the Shah dynasty and a deeply rooted centralized political system. This shift was driven by the need to become more inclusive and form a representative government, but Nepal struggled with implementation.

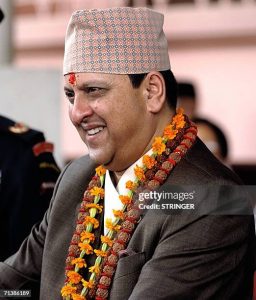

Let’s look at the reasons why federalism is a hard-to-swallow pill for the people of Nepal. One of the biggest reasons is the tradition of authoritarian government. The political history of Nepal has been shaped by this government structure for centuries. Looking back at history, since the 18th century, under the Kingdom of Gorkha, the Shah dynasty established absolute monarchy. In the 19th century, this changed as the Rana regime started, which reduced the monarchy to a symbolic role only, but the rigid authoritarian system was still there. The Rana rule ended when, in 1951, the Nepali Congress Party led a revolt, but no democratic reforms were seen because the monarchy had a strong hold over the political and government structure. 1990 was a turning point for Nepal because King Birendra accepted a multiparty democracy alongside the monarchy, and when everyone thought this was a period of political opening, he was assassinated, and again, executive control was taken by King Gyanendra. So, for much of its history, Nepal lacked democratic institutions necessary for federalism to function effectively, making this shift in political structures a radical departure from the past.

Deep-rooted centralization in the country is the second reason why federalism in Nepal looks unrealistic. For centuries, power was concentrated in Kathmandu, which meant that other regional and ethnic groups had little autonomy. Some exceptions existed, termed as concessions made by Nepali rulers to specific communities, e.g., the Limbus, who maintained a level of autonomy through the Kipat land tenure system. The highly famous Panchayat system, introduced in 1960, was a four-tier hierarchical system that claimed to promote democracy but ultimately reinforced state control. The system focused on establishing local councils, but all of these were closely tied to the central government structure. So, in the 1990s, Nepal had many administrative units, such as District Development Committees, but they served as tools of political control rather than genuine efforts at decentralization. This stronghold of centralized power meant that when moving towards federalism, the country needed to dismantle the deeply entrenched political norms of the state.

Beyond centralized governance, another major issue was that Nepal’s political structure was highly dominated by a narrow elite, making federalism difficult to fit in. Nepal is diverse in ethnicity; it is home to people of various races and colors. However, for centuries, it had been controlled by a small segment of the population, consisting of the high-caste Hindus—the Brahmins and the Chhetris—who make up 31% of the population. After the Rana regime ended, state policies often reinforced this dominance through the recognition of Hinduism as the state religion and the push for “Nepalization,” which marginalized ethnic minorities and lower-caste groups. These practices fueled resentment among the public and increased demands for a more inclusive political system.

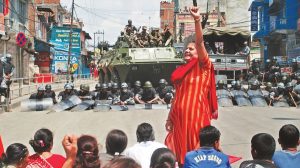

Despite facing all these barriers, Nepal embraced federalism in 2007. The decision came in the wake of a decade-long Maoist insurgency that called for radical political and social change. A significant movement that rose in 2006, also known as the People’s Movement, led to elections for a Constituent Assembly in 2008, and their main aim was to restructure the state. At that point, federalism emerged as a necessary response to Nepal’s complex social fabric.

The decision to adopt federalism was momentous, but conflicts arose when the structure of the federal state was decided. The number and boundaries of Nepal’s federal units became a major point of debate. Various maps were proposed by different political and civil parties—some suggested as few as three provinces, while others advocated for up to 25. The central issue that kept arising was whether federal units should be drawn based on ethnic identity or territorial considerations. Even in the early 2010s, the CA’s committee for restructuring the state proposed a federal map with 14 provinces, named after ethnic groups. However, competing visions led to disagreements and delayed the finalization of the federal state.

Nepal’s transition to federalism was unexpected given its history but was ultimately driven by the need for a more inclusive governance system. This shift has helped bring marginalized groups into the political fold, but the challenges haven’t ended. Questions regarding the nature and number of federal units highlight deeper concerns about identity, governance, and representation. As Nepal continues refining its federal system, the coming years will be crucial in determining whether federalism is successful.