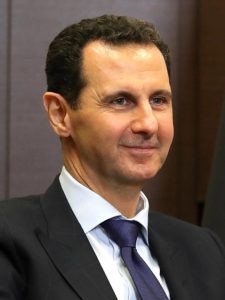

When the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and their allies stormed Damascus in December last year, Western capitals rejoiced at the fact that a major Russian ally had been deposed. President Bashar al-Assad, who had fled to Moscow just hours before the fall of his capital after a long and bloody civil war, was regarded by Western commentators as a dictator and tyrant, accused of committing atrocities against his own people.

The Syrian Civil War began in March of 2011, during the larger Arab Spring that saw longtime rulers like Libya’s Gaddafi and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak removed from power in large—and often violent—displays of public opposition and protest. The Arab Spring shaped the Middle East into its present condition, weakening many states and even collapsing some entirely. Among the many targeted regimes, President Assad was considered to have held onto power the longest, with the unequivocal support of Russia and Iran.

As is common with authoritarian regimes headed by members of a religious or ethnic minority, President Assad was accused of victimizing Syrian citizens based on ethnicities and religious beliefs. The accusations were tame compared to what the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) was doing around the same time, but the fact that some of the stronger opposition groups to Damascus were comprised of Sunni Muslims or Kurds made the charges plausible.

The new regime, led by HTS Commander in Chief Ahmed al-Sharaa—a former member of Al-Qaeda who fought against US forces in Iraq and led the Al-Qaeda-associated Al-Nusra Front in Syria—assured the world that Syria had turned over a new leaf. He appeared to the world as a moderate, making overtures to the West and releasing many of the political prisoners held by the previous government. For the last few months, the attention of the world slowly moved away from Syria, with some saying that the country was on the path to healing itself and tending to its wounds.

On Friday, however, reports emerged of unrest in the country’s coastal Latakia Governorate. The governorate is a stronghold of the Alawite sect of Muslims, the branch of Shiite Islam adhered to by the former President and his family. President Assad is also a native of Latakia, which explains the presence of loyalist outfits long after his departure.

According to sources within the HTS-led government, cited by Al Jazeera, a series of insurgent ambushes killed 15 security personnel this week. The government launched a clearance operation in Latakia, which the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) claims has killed over 1000 people, including over 700 Alawite civilians who are believed to have been summarily executed by the new regime. Videos and photographs of these executions have surfaced, showing young boys being shot and beheaded by the regime; videos of HTS members ‘bombing’ civilian areas by tossing explosives out of helicopters have also emerged.

This development, however, has largely been overshadowed by other developments, principally an address by the current Foreign Minister of Syria to the Organisation for the Prevention of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). Speaking at the Hague, Minister Assad Hassan al-Shibani pledged that his government would definitively end Syria’s chemical weapons program and destroy any stockpiles leftover from the previous government. The move has been hailed as a historic departure from Syria’s insistence on maintaining banned chemical weapons—the Assad regime insisted the weapons were for national defense, while most sources agree that the weapons were used against rebel population centers during the civil war.

The European Union and the United Kingdom have also responded favorably to the new regime, with the UK removing sanctions placed on several Syrian entities such as the Syrian National Bank, Syrian Arab Airlines, and several Syrian companies involved in the production and trade of energy products this week; the EU had taken similar steps late last month.

While it is unclear how prolonged the insurgency in Syria will end up being, or indeed how it will end, the international community has an obligation to investigate the tactics being used. Should the new regime fail to live up to its promises of respecting human rights, necessary steps to pressure the government into honoring their pledges should be taken.