China-Pakistan Economic Corridor will be a game changer,” said former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. CPEC was hailed as the flagship economic project when it was first announced in 2015 to the tune of $46 billion. It was the project that would unlock Pakistan’s economic potential, launch the nation—facing decades of economic turmoil, artificial growth, lack of investment—and, most importantly, connect the country to the untapped markets of Central Asia, finally catapulting Pakistan into the ranks of nations poised to take the economic world by storm. A dream that everyday Pakistanis repeated ad infinitum to anyone who bothered to listen. And why not? Indeed, more than the energy projects, infrastructure investments, or even the cynical view of shifting patrons from America to China, the main selling point—the pitch—is connectivity to Central Asia.

The vision of lorries, trucks, and freights transporting gas, oil, minerals, and other goods from the markets of Central Asia to the ports of Pakistan and vice versa isn’t a far-fetched desire. Indeed, it is rather plausible, given centuries of trade between Central Asia and the regions of Pakistan when caravans ruled global trade before maritime colonial powers shifted it to the blue seas. Yet, this goal is based on a dangerously unstable foundation—the gamble our policymakers played. So, what is the crack in this perfectly crafted mosaic? What is the puzzle piece that stubbornly refuses to fit in the picture? It’s not the corrupt bureaucracy, political turmoil, or even Balochistan’s security problem. No, the circle that refuses to square itself is Afghanistan.

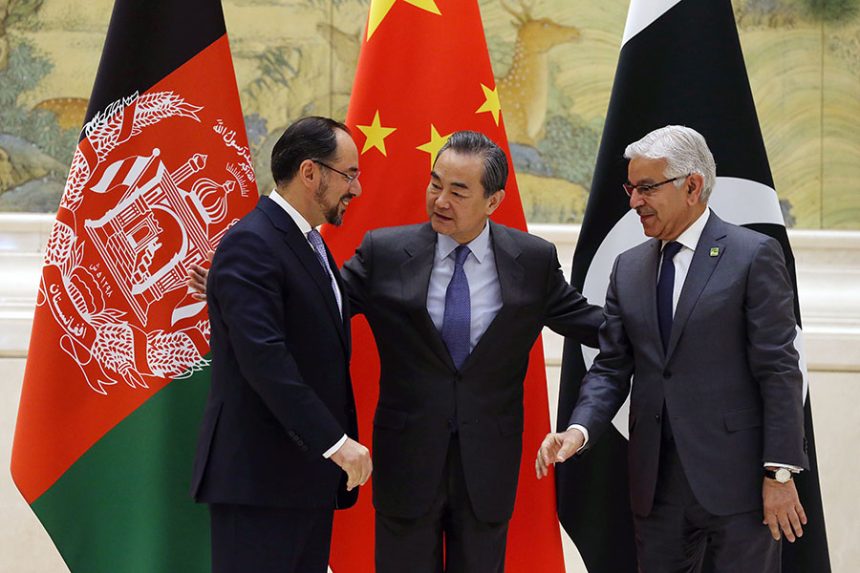

Look at any map that proposes trade and pipe networks from Pakistan to the Central Asian countries. Almost all, if not all of them, go through Afghanistan. To fully appreciate the Afghanistan conundrum, one must understand that it isn’t the first time the problem of Kabul threw a wrench into such connectivity. With the collapse of the U.S.S.R. and the emergence of the new Central Asian Republics (CAR), Pakistan was presented with an opportunity it could not give up and immediately signed at least six MOUs with CAR nations. Just like the Chinese of today, Americans—more specifically, oil companies like Unocal—blessed these adventures, with such interests manifesting in the form of the Pak-Turkmen oil pipeline. Yet, all these ideas and MOUs faced a critical obstacle, and that was the conflict in Afghanistan. By 1992, Afghanistan had descended into civil conflict between various Mujahedeen groups, and warlords had carved up the country into hundreds of small fiefdoms. In such a tapestry of instability and division, policymakers in Islamabad made a decision that affects the country to this day: support to the Taliban.

It was perhaps hoped that the fundamentalist militia would have the capacity to unify the country and create an environment of security, albeit one where the Afghan people had to contend with an oppressive regime. Unfortunately, rather than bring peace and security, the Taliban fought a brutal civil war against opposing factions and, most damagingly for Islamabad, the Taliban’s Islamic radicalism and close ties with jihadist international groups were seen as a threat by CAR nations. The opportunity of the 90s thus collapsed, and with the American invasion in 2001, any such hopes to revive them were forestalled.

With the signing of the Doha deal in 2020 and the subsequent withdrawal of American troops in August 2021, there was much jubilation in Pakistan, not only over the supposed end of the war in Afghanistan but also because of the prospect of completing the original intent of CPEC. Finally, the barriers to trade had been removed. And unlike the 90s, the Taliban were called reformed and controlled the entirety of the country, where previously the north was in the hands of the aptly named Northern Alliance before the American invasion. Most importantly, China seemed poised to flood Afghanistan with investment and aid, thereby stabilizing it and persuading the country to join CPEC and perhaps finally realize the dream of Central Asian connectivity.

Fast forward to 2024, and these notions seem to be premature. It was said that America left Afghanistan in defeat. The author disagrees with this statement; they left it as a tinderbox that requires just one spark to blow the region up and end the prospects of CPEC for a long time. The Taliban weren’t reformed, as evidenced by the ban on girls’ education. Internal security didn’t come, as attacks by Daesh continued, paired with other insurgent groups. Unity didn’t come, with new and old factions challenging the Taliban’s rule in the north and central provinces. Countries have shied away from recognizing the Taliban, and American sanctions have collapsed the economy, with 90% of Afghans in danger of starvation. Most critically, the Chinese seem to have taken a cautious stance, emphasizing diplomacy while only gradually strengthening economic ties.

In all of this, the Americans left behind almost $7 billion worth of weaponry, whose only overseer is a recently transformed radical insurgent group. The destabilizing effect is best illustrated by seeing insurgent groups in Pakistan suddenly using American equipment while attacking state security forces. As the cold war between China and America intensifies, and Washington seeks to resurrect George Kennan’s policy of containment, it would seek to disrupt Chinese investment and create instability at its peripheries. In this new great game between superpowers, Afghanistan will be the Achilles’ heel of CPEC. The Americans need only give a few guarantees and open the tap of financial support to opposition factions to shatter the tenuous control of the Taliban over the country and plunge it into fresh conflict.

Or perhaps American interference isn’t even required. Regional powers may light the spark themselves for their interests. The Taliban are fundamentalist and uncompromising in their attitude, an attitude that might cost Afghanistan a peace it has sought for four decades. Rejecting any and all political accommodation with the opposition while monopolizing power in the hands of their Pashtun-dominant leadership means there are significant political and ethnic fault lines to ignite. Indeed, opposition factions like the National Resistance Front have their leadership in Central Asian republics, countries that have acute concerns with the Taliban regime. Afghanistan is known to host militants from jihadist organizations who have waged bloody campaigns against the governments of CAR nations, and the Taliban have been long accused of hosting them, especially the Tajikistani Taliban and Al-Qaeda.

More critically, as tensions increase between the Afghan Taliban and Islamabad over cross-border attacks by TTP and the Durand Line issue, there is a very real chance of Pakistan joining certain Central Asian countries and supporting anti-Taliban forces, leading to a repeat of the 90s and its ominous consequences.

The success of CPEC—the actualization of its aim—rested on one gamble: that Pakistan and China would be able to tame and stabilize Afghanistan. Yet, given the track record of foreign powers influencing Afghanistan and the inherent fissiparous nature of the country, such a gamble might not pay off. The tinderbox of the region is too dry, with too many actors willing to light the matchstick. When the agreements were signed in power corridors between Beijing and Islamabad, it was hoped that our policymakers could navigate the graveyard of empires. Yet, now it seems we will be proving Mark Twain’s famous saying right:

“History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”