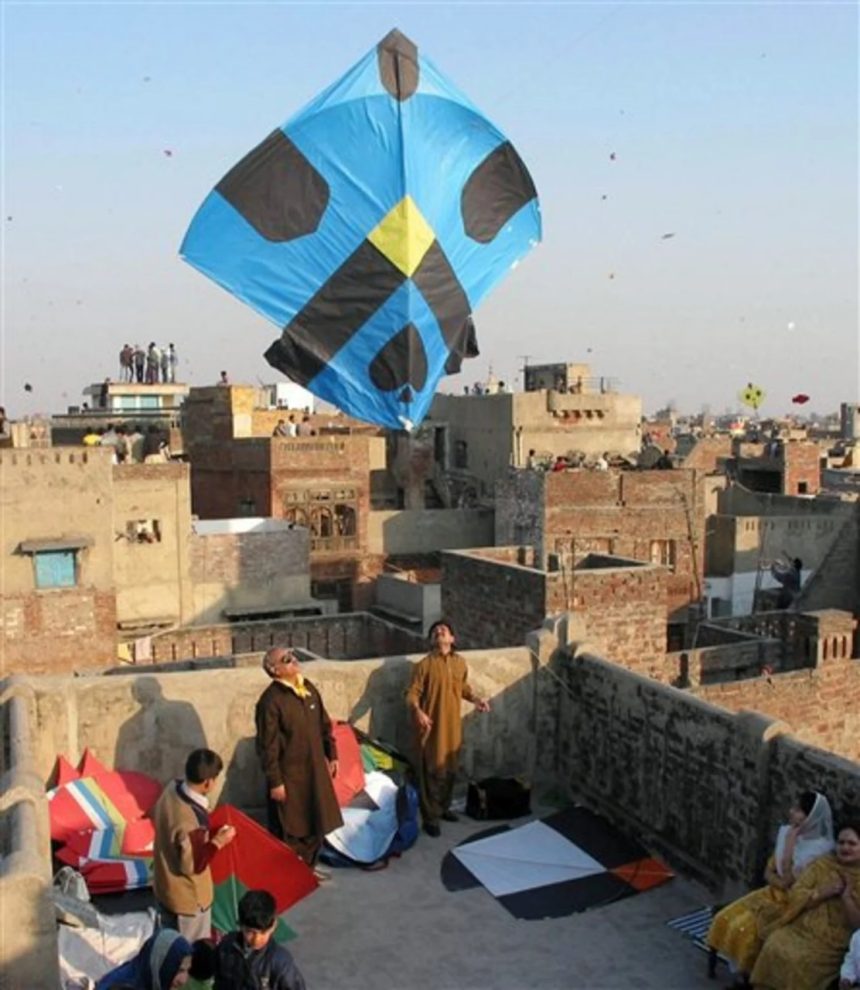

“BO-KATTA! BO-KATTA!” was all that we could hear sitting in the baramda of my house in my hometown, deep in southwest Punjab. The sound of kids running and laughter filling the air confirmed the awakening of Basant. The bright sun, lush green kikris, and the pearly white safaida, along with the golden sarsoun, provided a rare sight for its observers. However, the crowning glory was the stark blue sky laden with colorful kites, embroidering the landscape with a kaleidoscopic view. Standing under such a sight made me wonder—how did this tradition come into being?

Origin of Basant

The answer to Basant’s origin can be traced back to Vasant Panchami, the Hindu festival of the spring season. Literally meaning “the fifth day of spring,” it is celebrated on the fifth day of the Hindu month Magh (February). This season symbolizes life, as nature restarts its cycle, giving way to new existence. According to some accounts, Basant has been dedicated to the Hindu goddess of knowledge and wisdom, Saraswati, a consort of Brahma, who, according to Hindu traditions, is the creator of the world. Being born on the fifth of Magh, Basant is celebrated to honor her birth.

Although other historical accounts regarding Basant’s celebration do exist—some claim that Basant was an aftermath of solidarity with the death sentence of a Hindu blasphemer—the former notion is the one that is more widely believed.

Dark Side of Basant

With Basant’s vibrant energy rejuvenating everything around, there is a dark side that has turned this vibrant festival into a death sentence for many. Initially, the string (dore) used for flying kites was made out of plain cotton and was not harmful to others. However, as competition grew among kite runners, the dore started being manipulated into sturdier forms. This led to the creation of a special type of dore known as manja.

The difference between the two is that the thread used for manja is covered by a lep (layer), which mainly consists of crushed glass and metal mixed with an adhesive. This layer provides a more robust structure to uphold the kite more strongly, and because of its razor-sharp structure, it is able to cut the strings of other kites as well, helping its users win competitions of this sort. However, this manja has severe consequences, with many people losing their lives. Being thin and razor-sharp, it can easily cut through thick flesh, as was the case with many Pakistanis.

Since the 2000s, a rise in the use of manja has been observed, and as a result, the rate of deaths has also increased dramatically. Bilal Khan, a victim of a similar attack, reports how, many years ago in Lahore, he faced a similar occurrence where, while riding a bike, a manja cut through his hand and would have reached his throat if it weren’t for the thick jacket he was wearing. This isn’t just an isolated event—many have been reported killed in similar incidents.

Legal Action

To reduce such events, the government took action by bringing an amendment to the Prohibition of Kite Flying Act 2007 in 2024. This entailed that people caught flying kites could face up to five years in prison or a fine of 2 million rupees. Moreover, individuals involved in making and transporting kites can face up to seven years in prison or a fine between 500,000 and 5 million rupees. The law also states penalties for minors, with the first offense resulting in a warning, the second in a fine of 50,000 rupees, the third in a fine of 100,000 rupees, and the fourth in imprisonment.

Conclusion

Although these laws are made to save lives, they aren’t as efficient. The main reason behind this may be the lack of strict enforcement. This is evident in how kites can still be seen flying in rural areas almost regularly. A better approach to this problem would be to strangle the root cause, which, in this case, seems to be the glass-coated manja. The manufacturing of this material should be strictly banned, and harmless cotton threads should be provided as an alternative. In this way, the culture can be celebrated without harming any lives in the process.

Working towards more sustainable changes rather than opting for quick shortcuts that cannot even be properly implemented should be prioritized to reinforce long-term development.