The decorations have decked every room in your house—strings of marigolds and fairy lights cascade down the walls, people are coming and going, and the hustle and bustle of shaadi prep has taken over all the women in your family. It’s a sensory fever dream. You’re sitting at a dholki, in a circle of girls your age and older, with one of them at the centre of attention, rhythmically beating a dhol.

One of the most important aspects of South Asian weddings is the music we play. These songs, timeless in their very essence, are somehow memorised by heart and become the icing on the cake—the celebration of a union between two people, two families, and all that they share. These tracks form a map of gender roles across generations, their lyrics carrying nuanced ideas of femininity amidst the glitter of gold organza and shaadi ke laddo.

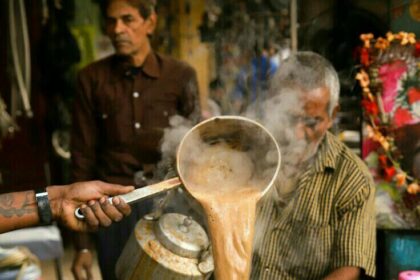

They start singing Mehndi Hai Rachnewali—a staple mehndi song across subcontinental cultures. Can it be a wedding without this song on repeat? Absolutely not. But as you grow older, you start thinking about what the song actually says. In Alka Yagnik’s nightingale voice, it sounds like a lullaby sung by a bride’s mother as she sits at her mayoun. But it’s more than that.

Tere man ko, jeevan ko, nayi khushiyan milne wali hain / Teri mehendi wo dekheinge toh apna dil rakh deinge wo, haryali bani.

As the title suggests, the song emphasises the presence of mehndi (or henna), describing how the red pigment enhances the bride’s inner beauty. The groom, upon seeing her adorned in it from head to toe, is said to fall at her feet. Much like other songs of this genre—such as Mehendi Laga Ke Rakhna—the implication is that mehndi has a magnetic, even submissive, power. Yet in that same song, the girl’s part sets an assertive tone: she demands the man be ready and not say a word until he stands at her doorstep. That’s some early Bollywood girl power right there.

These songs are etched into our psyche—catchy, sharp, and clever. Still, most paint the bride in a state of coquettish reluctance, as if her “yes” is inevitable, and the groom is a macho man who won’t take no for an answer. He’s strong, loud, boisterous—his conviction unshakeable when he says, Lene tujhe, o gori, aayeinge tere sajna—as if not even Simran’s father’s disapproval could stop Rahul.

Femininity is often portrayed as fragile as glass roses—existing only in contrast to its masculine counterpart. But times are changing. Newer songs like London Thumakda and my personal favourite (still missing from most mehndi medleys), Naram Kalja, shift that dynamic.

This revolution in the genre brings a cheeky reclamation of what femininity means. The lyricism introduces conversations about consent, no longer kept in the background. Here, the woman flips the narrative, telling the man he is merely a source of pleasure for her—and nothing more. (Ouch.)

Take Amna Riaz, a Pakistani singer-songwriter, who curated a vibrant mix of songs to sing and dance to at her own wedding. Having grown up with the internet, she sang an italicised, pseudo-American-accented version of the iconic mayoun song Kabira from Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani. The song, split in two halves, first scolds the groom, Kabira, for leaving—calling him selfish and insolent. The second half becomes a melodious farewell to Banno, the bride, wishing her joy and prosperity as she departs in her red lehenga.

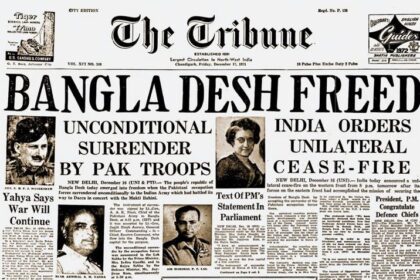

We’ve grown up with these songs—and as we’ve changed and progressed, so have they. It’s no longer taboo for a bride to dance at her own dholki, to smile and beam at her guests. It’s her wedding! Let her smile! Gone are the days when she had to sit meekly beside her soon-to-be husband, as if all the glittering processions were happening against her will. This positive shift is reflected in the music we choose—songs that redefine gender norms and dissolve the shame our mothers and grandmothers once felt at weddings.

All in all, it’s safe to say we’ll keep singing these songs—remixing and melting them into the beat of our own rhythms. Maybe even play something FEIN at a dholki. Why not? Who’s going to stop us?

Wow, Zaynab! This is nicely written and well described. I will look forward to reading more from you.

Asim Khan

Impressive read. Keep up the great work..

Amazing work! So proud of you.