“Well-behaved women seldom make history.”

— Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

In Pakistan, a “good” woman isn’t merely an idea—it’s a handbook, a script authored decades before she is born. From dressing to talking, from what she decides to pursue to the dreams she dares to chase and the ambitions she suppresses, every move in her life comes under a phantom microscope, critiqued with the rigid standards of morality, honor, and tradition.

On the surface, these expectations may appear innocuous—maybe even altruistic. But in fact, they are shackles, designed with precision to limit a woman’s autonomy, her decisions, and ultimately, her identity.

“Log Kya Kahenge?” – The Fear That Controls Lives

If Pakistani women were paid a rupee each time they heard “Log kya kahenge?” (What will people say?), they would be wealthy enough to purchase the liberty that society so frequently withholds from them.

This sentence is not a casual remark—it is a force that governs every important choice in a woman’s life. It decides whether she can pursue a career, whether she can leave the house unaccompanied, and even whether she is allowed to laugh too freely in public.

A girl returning late from work?

“Achhi larkiyan raat ko bahar nahi rehti.”

(Good girls don’t stay out late.)

A woman prioritizing her career over marriage?

“Koi masla hai kya? Koi larki itni dair single nahi rehti.”

(Is something wrong? No girl stays single this long.)

A wife not giving up her ambitions?

“Aurat ka asli maqam ghar hai.”

(A woman’s true place is in the home.)

These phrases, habitually uttered by family members, neighbors, and even strangers, construct a woman’s reality from a young age, long before she can define it for herself.

The Ideal Daughter, Sister, Wife, and Mother – A Role with No Space for Self

The expectation to be a “good” woman is instilled from an early age. A good daughter is seen and not heard. A good sister puts dreams on hold to support her brothers. A good wife does all without complaining. A good mother puts her kids first, even before herself.

And if the woman has the audacity to put herself first? She is selfish. Noncompliant. Too progressive for her own well-being.

An ambitious young woman who wishes to study overseas?

“Itni door akeli kaise jaogi? Achhi larkiyan ghar ke paas rehti hain.”

(How will you go so far alone? Good girls stay close to home.)

A woman divorcing a violent husband?

“Shaadi nibhana aurat ki zimmedari hai.”

(It’s a woman’s responsibility to sustain a marriage.)

The message is unmistakable: A “good” woman will suffer in silence. She will adapt. She will remain within the parameters that have been set before her.

The “Good Woman” Myth: A Mechanism of Control

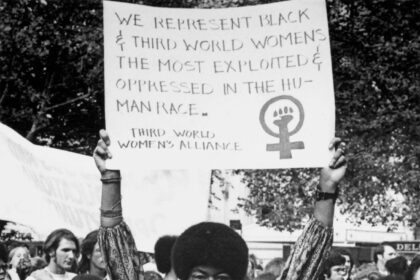

For centuries, society has prescribed what it means to be a “good woman”—not as an expression of virtue, but as a mechanism of control. Women who do what is expected of them are rewarded, while those who push back against these expectations are labeled as difficult or rebellious.

A so-called “good” woman is supposed to be deferential, meek, and obedient. She learns that she is valuable to the extent that she can serve others—be it as an obedient daughter, a devoted wife, or an altruistic mother. On the other hand, women who assert themselves, strive for their dreams, or defy injustice are relegated to the side, labeled too aggressive or too radical.

But who determines what makes a “good” woman?

Traditionally, these norms have been established by patriarchal systems—families, communities, and institutions that benefit from dominating women’s decisions. The idea has never really been about respectability; it has always been about compliance. Women are asked to forgo their autonomy and even their health in order to sustain an illusion of respectability.

But why is a woman’s value determined by how well she measures up to someone else’s standards? Shouldn’t she determine it herself?

The “Good” Woman vs. The “Bold” Woman

A woman in Pakistan navigates between being “good” and being “bold.” And “bold” is never a virtue.

A woman who stands up against injustice?

“Besharam.” (Shameless.)

A woman who bears silently?

“Sabar wali.” (Patient.)

The burden of respectability is always placed on women. Men, on the other hand, enjoy the freedom to live as they please, without the same societal constraints.

According to a 2024 report by the World Economic Forum, Pakistan ranks 145th out of 146 countries in gender equality, highlighting the deeply entrenched discrimination that continues to limit women’s opportunities. A 2022 Human Rights Watch report found that 32% of Pakistani women experience domestic violence, yet cultural norms discourage them from seeking help.

Overcoming the Stigma – The New Wave of Change

But despite the entrenched notions, a new generation of women is resisting. They are demonstrating that being a “good” woman is not about erasing themselves—it’s about owning their truth, their freedom, and their choices.

Women in Pakistan are succeeding in all areas—medicine, engineering, literature, business, politics—despite the voices of discouragement that tell them they shouldn’t.

Social media, literature, and activism are rewriting the script. Women are openly discussing their struggles, breaking taboos, and supporting each other in ways that were once unheard of. Younger generations are slowly redefining what it means to be a “good” woman—one who is strong, independent, and unafraid to stand up for herself.

Conclusion – Redefining What It Means to Be “Good”

The shame of being a “good” Pakistani woman isn’t so much about expectations as it is about control. It’s about telling women what to do, instead of allowing them to decide for themselves.

But change exists. It’s slow, but it’s real.

Every woman who stands up to be counted despite being bound by traditionalism is shattering this shame. Every woman who chooses dreams over approval is redefining the code.

And perhaps, someday, being a “good” woman will be no more than to be herself—with no fear of “log kya kahenge?”

Now is the time to stop teaching women to compromise and begin empowering them to truly live. It is time for women to define their own narratives, instead of following a script written for them.

The pervasive question, “Log kya kahenge?”, has long been a tool of control, dictating women’s choices and suppressing their autonomy.

Your call to redefine what it means to be a “good” woman essential especially in this time Empowering women to live authentically, free from the fear of societal judgment, is crucial for fostering a more equitable society.

Noor ul Taba such a thoughtful message!