Human history is a testament to our continuous pursuit of finding concrete answers to questions that are complex. Measuring human intelligence is a complex task, and our effort to simplify it has traditionally limited it to a few standardised intelligence tests. As Arundhati Roy writes, “To never simplify what is complicated and never complicate what is simple,” we should try thinking beyond our established notions of intelligence and not simplify it to a few numbers.

IQ stands for intelligence quotient. It is a score derived from standardised tests designed to assess human intelligence, and it evaluates various cognitive skills and yields a result to gauge a person’s potential and intellectual capacity. Contrary to popular belief, the intelligence quotient (IQ) is not an objective indicator of intellect. Since intelligence is an abstract trait, it can not be accurately quantified. Over the years, realising this limitation, researchers have been trying to improve their understanding of the structure of intelligence starting in the early 1900s. Significant test sets have been created to evaluate other aspects of our brain’s functioning, such as working memory, verbal and visual-spatial operations, and several activities that are used in current tests to determine a person’s intellectual ability. Still, there is no one test to assess intelligence since it stems from so many diverse emotional and experience sources, and IQ levels may not always indicate intelligence. IQ tests might help practitioners in identifying disabilities, but they cannot measure the full capacity of a functioning brain.

As long as the test is concerned, the score is a relative metric that indicates a person’s position concerning the group average of 100. There are many unknowns around an IQ test as well, like the circumstances surrounding its administration, its intended goal, intentional or unintentional mistakes committed, etc.

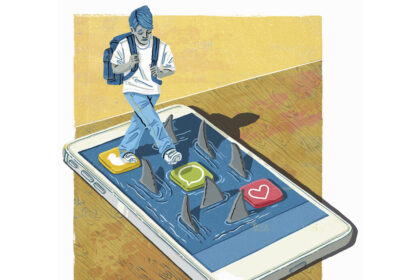

Using IQ tests to measure intelligence in the education system has a deep-rooted cultural bias as well. Those who go to private tutors and tuition centres learn the tricks to score higher on the tests and eventually end up scoring well, making it more a test of the quality of education and memory. These tests are also claimed to be skewed against minority children, mostly Black, followed by Hispanic, based on culture, language, and economic status in many countries, and racial and ethnic differences in IQ results are proof of this racial bias. Around the world, many talented minority children are claimed to be excluded from gifted education programs because of the biased IQ testing, which exacerbates success inequality. Despite having certain natural qualities, intelligence can only grow in a supportive environment. Families, schools, and the social environment all have important roles to play. Since intelligence is correlated with schooling and the social and familial environment, it is impossible to test IQ without considering these factors. While this may seem unfair, it is a fact that is evident in other fields as well: offspring of professional musicians and athletes will more readily acquire athletic abilities.

IQ testing has historically shown some gender-based differences. Women often excelled in verbal tasks, while men tended to perform better on tests of spatial ability—the capacity to mentally manipulate objects in three dimensions. However, these disparities have largely disappeared, suggesting that any inherent gender-specific cognitive orientations are not supported by scientific evidence.

Moreover, the IQ testing system tests students in linguistics and mathematics. Students with a better creative art side are overlooked throughout this testing process, which also makes this testing method invalid. Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences proposes that intelligence is not a single, fixed trait but rather a pattern of distinct abilities. He identified eight different intelligences, including linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinaesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. This theory challenges the traditional view of intelligence as well, which is primarily focused on logical and linguistic skills.

Therefore, a single score is insufficient to adequately represent intelligence, as it is a complicated quality impacted by various emotional, cultural, and experience elements. More inclusive and fair approaches to evaluating intellectual capacity are required because of the inherent biases in IQ testing, which are especially detrimental to minority groups and people from diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds.