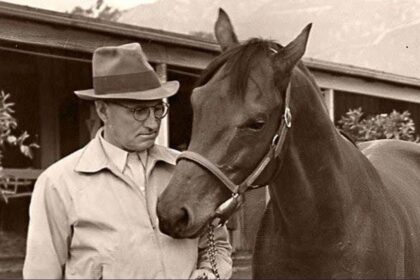

Captain Jack Seely, age twenty-six, rode his horse Warrior into battle at Passchendaele on November 6, 1917.

Warrior was an eight-year-old bay gelding, Jack’s mount for two years—an animal that had survived countless battles and become Jack’s closest companion in the hell of the Western Front. Horse and rider shared a bond that went far beyond military necessity. Warrior often seemed to understand Jack’s commands before they were given; Jack could read Warrior’s moods and fears as clearly as his own. Together they had crossed shell-torn fields, endured artillery barrages, and escaped death more times than Jack could count.

That morning, during a cavalry charge into the German lines, Warrior stepped into a shell crater hidden beneath mud and debris. Barbed wire lay buried at the bottom. The horse’s legs became entangled, and the sucking mud began to pull him down—the same mud that had swallowed thousands of soldiers at Passchendaele.

Jack dismounted instantly. He tried to pull Warrior free, but the horse was trapped, the wire biting into his legs, the mud tightening its grip.

Machine-gun fire swept the field.

Jack’s fellow cavalrymen shouted at him to leave the horse, to save himself. They told him Warrior was only an animal, that Jack was risking his life for livestock.

But Warrior was not “only an animal” to Jack.

This horse had carried him through two years of war. He had never broken under fire. More than once he had saved Jack’s life by sensing danger before Jack could. Jack could not abandon him to drown slowly in terror and pain.

“I’m here, boy,” he whispered, pressing his forehead to the horse’s neck. “Easy. I won’t leave you.”

For forty-five minutes, under direct machine-gun fire, Jack worked to free him.

He cut at the wire with his knife. He dug mud away with his bare hands. He spoke constantly, trying to keep the panicking horse still as bullets snapped past his head. Other soldiers who tried to help were shot or driven back by the intensity of the fire. Jack’s commanding officer ordered him to leave the horse and retreat.

Jack refused a direct order.

He chose court-martial over abandonment.

Finally, bleeding, exhausted, and half-buried himself, Jack cut through the last strand of wire. With a strength born only of desperation, he hauled Warrior upward. The horse scrambled, found purchase, and lurched free from the crater.

Both were coated head to hoof in mud, blood seeping from dozens of wire cuts—but both were alive.

Jack led Warrior back toward the British lines under continuing fire. Somehow, they survived.

Jack Seely was formally reprimanded for disobeying orders, though not court-martialed. His commanding officer later admitted privately that he would have done the same for his own horse.

Warrior survived the war—one of only sixty-two thousand out of more than a million British horses sent to the front who ever returned home.

After the war, Jack retired Warrior to his estate, where the horse lived in peace until dying of natural causes in 1941 at the age of thirty-two.

In 1934, Jack published a memoir about Warrior and dedicated it:

“To Warrior, who carried me through hell and taught me that courage is not uniquely human, that loyalty transcends species, and that sometimes the bravest act is refusing to abandon those we love when survival demands it.

I risked my life for a horse, and I would do it again without hesitation.

Warrior was not just an animal. He was my brother in arms.”

Jack Seely died in 1947 at the age of fifty-six, requesting to be buried near where Warrior was laid to rest.

Warrior’s grave bears a simple stone:

“Warrior — 1909–1941

War Horse

Survivor of Mons, the Somme, Passchendaele

Faithful companion who carried his rider through hell and back.”

In 2014, a memorial to war animals was unveiled in London, with Warrior honored as a symbol of the million horses, mules, dogs, and pigeons who served and died in the First World War.

At the unveiling, Jack’s grandson said:

“People said my grandfather was crazy—that a man’s life is worth more than an animal’s.

But my grandfather understood something profound.

Warrior was not just a horse. He was a fellow sufferer. A fellow survivor.

Abandoning him might have saved my grandfather’s body, but it would have destroyed his soul.

He chose his soul over his safety.

That is not madness.

That is love.”