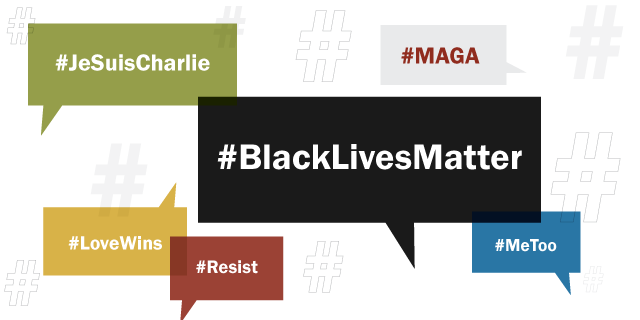

In a time when social media is the primary platform for initiating modern activism, street protests typically take place on social media. A hashtag — short, sharp and shareable — is the cry of thousands. It can be a movement such as #MeToo, a movement such as BlackLivesMatter, a movement such as FreePalestine, or a movement in a local Pakistani city that highlights the issue of gender violence and political injustice, but digital activism has become the new hallmark of the modern protest culture. However, as these hashtags go viral across the world, there is a disturbing question of whether online activism really does change reality or merely gives the illusion of movement among people.

At its most idealistic, hashtag activism is radical. It demolishes the conventional boundaries of authority by providing the common man an avenue to voice his opinion. To teenagers in Lahore, students in Karachi, or even scavengers in New York, access to world audiences is equal. Narratives that were kept in the shadows are spreading, and media houses, governments, and the masses have to deal with matters they previously ignored. The internet’s speed allows movements to spread quickly, attracting individuals from various continents within minutes. The result is a potent visibility, which does its work in educating, in alerting, and in mobilising.

However, being visible is not a change. Social media thrives on emotion and urgency, yet the transformation of society requires patience, organisation, and persistence. A lot of digital theorists encounter what activists refer to as “slacktivism” — the propensity of individuals to go ahead and click, like, and share without being meaningful. A hashtag will trend for up to 48 hours, but the effect tends to wear out when people switch to the next viral event. The initial surge fades away, transforming into a digital phenomenon rather than a tangible one.

Hashtags can start movements, but they can’t sustain them. Offline tactics include community organising, grassroots engagement, legal organising and institutional pressure: these tactics are essential. Examples like the successful #MeToo movement only resulted in sustainable consequences as survivors went to the mic, organisations changed their policies, and legal systems were required to be answerable. Similarly, street demonstrations, petitions, and grassroots efforts have long been effective in bringing about structural change without relying on hashtags.

In Pakistan, hashtag activism follows the same trend. From campaigns against honour killings to solidarity efforts by students, online outrage can generate awareness but often struggles to lead to action without organised follow-ups. A trending hashtag can trigger a national discussion, but some of the most long-standing problems, like gender inequity, censorship, or corruption, need long-term interaction, citizen engagement, and policy changes. The strength of the hashtag is amplification, rather than execution.

This does not imply that digital activism is a waste of time. Instead, it is a starting point rather than an endpoint. Hashtags are instigators — they start a conversation, unite groups and break the silence. However, to transform a trending movement into tangible change, we need to combine online fervour with offline determination.

Ultimately, hashtag activism has been a two-sided sword, empowering but limited, loud but short-lived. Its real potential is only realised when cognition becomes actual and digital manifestations become real-life transformations. Our generation has the challenge of bridging this gap by making sure that whatever trends online really make a difference in life offline.