Urdu — once the language of poets and philosophers — stands at a digital crossroads, caught between the glow of new technology and the fading ink of its own script. The claim that the Urdu internet is dying is not entirely accurate, though it does face challenges related to language usage and digital adaptation. While Romanised Urdu is prevalent in online communication, concerns exist about the decline of the traditional Urdu script and its impact on the language’s future on the internet.

The survival of a marginalised language is yoked with the adaptation of new technology, to the effect of incorporating contemporary knowledge into society. Unfortunately, the popular perception of the Urdu medium as a symbol of lower status has hindered efforts to translate Western knowledge into Urdu. Moreover, if the increasing use of English has been perceived as linguistic genocide by many zealous religious leaders, teaching through the Urdu medium remains divorced from secular and technological education.

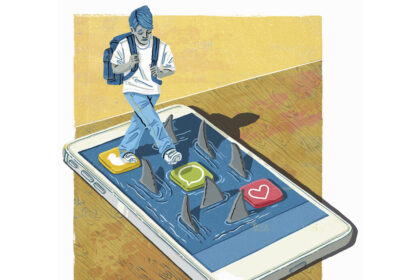

A close observation of the pattern of web browsing by Pakistanis reveals that the majority of accessed websites require basic knowledge of English, such as games, greeting cards, sports, and shopping etc. However, a small class of people with a good command of the English language utilise the language-rich websites for news, technology, information, etc. The majority of internet users are opting for romanised Urdu, Urdu written in a Roman script, for communication over cyberspace and SMS.

Mirza Ather Baig, one of the best Urdu novelists, says that all the languages of the world have been influenced by the communicative dimension of the digital lingo of cyberspace. Urdu and other endangered languages are not threatened by the dominance of English, but rather by the mindset of their literary practitioners, who largely fail to evolve and remain confined to their complacent world of traditional literary works.

Whereas language used to be a tool of territorial identification in the hands of nation-states, the internet has allowed its users the freedom to take control of their language by constructing their own virtual space. The younger generation finds the use of their ‘personalised’ style of writing liberating and cool, as opposed to having to adhere strictly to standard language in exams and other formal situations.

By skipping out on Urdu, students are unable to understand some of the greatest works in Urdu literature, such as those of Iqbal or Amir Khusro. What we see is people quoting English translations of Iqbal’s poetry, which often takes away its essence. No nation has ever progressed by working on someone else’s language. When we complain that our universities are not producing genuine scholars who make real breakthroughs in their respective fields, one of the reasons may be our detachment from our native language. As columnist and writer Orya Maqbool Jan says:

“You can learn in someone else’s language, but you cannot be creative in someone else’s language.”

The aim here is not to downplay the importance of English in any sense; it is only to point out that detaching ourselves from Urdu has cost us heavily. Studies on education systems have repeatedly shown that primary education in all subjects must be given in the mother tongue, as the child is best able to absorb it at that age. However, because we have not done so, due to our inferiority complex, we have failed to develop even a liking for Urdu among our current generation. Other than that, Urdu is the insignia of our culture. The unfortunate dilemma is that we consider it ‘cool’ or trendy to dissociate ourselves from it. If we compare ourselves to other non-English-speaking nations, such as Germany, France, China, Japan, etc., we can easily identify the deep sense of belonging instilled in them — one that we lack today because we are so confused.

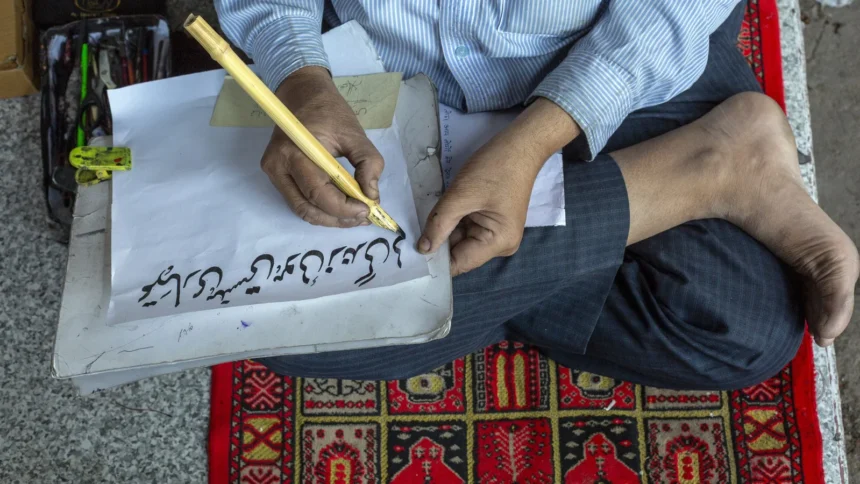

There is a relative scarcity of digital resources, like fonts and software that fully support the Urdu script, particularly the Nastalikq style, which is commonly used for writing Urdu. A broader decline in reading habits, regardless of the language, may also negatively impact Urdu and other languages. Some people also argue that there are gaps in Urdu education, which further leads to the decline in proficiency among some speakers, particularly in the younger generation. In certain contexts, the association of Urdu with a specific community or region creates a perception that it is not a language suitable for widespread use, including online.

While there are valid concerns that the use of romanised Urdu online is causing the real language to die with time, there is a greater need to support the Urdu script. The claim that the Urdu internet is a dying language is an oversimplification. There is a great need to give Urdu the opportunity to grow.