There is a silence that comes when you have lost everything. A silence so heavy and incomprehensible that you are left wondering how you keep on standing, witnessing as life slowly strangles you. You see it in the eyes of the farmer, standing knee-deep in what used to be his field — his livelihood — now a lake stretching to the horizon. His lips do not move. Nor does he complain. Yet, the stench of despair is evident in the air like humidity before the storm. In that silence lies the story of one of Pakistan’s greatest tragedies — not from nature, but from its own politics.

I recall being in seventh grade when a few of my senior classmates entered the room. They were carrying a box with them, and they told us that it was for collecting the “dam funds”. Luckily, I had a 100 rupee note crumpled in my bag, more money than I usually carried, and when I dropped it in the box, my heart was giddy with joy. I thought — mind you, I was a very naive kid with no interest in the world, except food — I had become part of something bigger than myself. We all did. We believed that we were contributing to a safer, more united Pakistan. What we didn’t know was that it was all a lie. There was no fundraising; the box was merely a magician’s prop, and both the money and the promise would ultimately vanish. Abracadabra. The dam never came.

Years have passed since that schoolroom moment, and yet Pakistan is still chasing shadows. Grand announcements about mega-dams — Kalabagh, Diamer-Basha, Akhori — every decade have marked the illusion of progress and hollow efforts. Kalabagh, in particular, took centre stage in these political theatrics: promised by generals, rejected by provinces, and cursed by technocrats. It became a weapon for our short-sighted politicians who were more interested in scoring points than solving crises. Punjab wanted it. Sindh saw it as theft and thus, on May 27, 2008, the government under the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) officially shelved the Kalabagh Dam project.

Federal Minister for Water and Power Raja Pervez Ashraf said that the controversy was so intense it threatened the unity of the federation. He said the allocated funds would be diverted to other projects if the dam had no importance in itself. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa feared drowning. Balochistan never trusted anyone. And so, the project — one that was undisputedly beneficial for our people — became less about water and more about identity, suspicion and control.

Meanwhile, the rivers swelled and shrank as they always have. Except that Pakistan had less and less space to hold them.

Over time, the country’s water storage capacity has reached dangerously low levels, barely enough for a month’s worth of supply, even though it is a recommended benchmark by the World Bank and FAO. Thus, every monsoon season and every surge of rain risks becoming a flood, combined with poor drainage infrastructure, and every dry spell a drought.

The catastrophic floods of 2022 exposed this failure with ruthless clarity. Officially, it was labelled a climate disaster, with unprecedented monsoon rains, swollen rivers, and glacial melts carrying the blame. But what they claimed was only half the truth. The other half of the truth was that it was man-made. Through deliberate negligence of our leaders, there were no reservoirs nor any dams to hold back the water — it was a preventable situation and still could have been avoided from its rebirth in 2025. It was the decades of paralysis that resulted in over 33 million people being affected and approximately 7.9 million people being displaced.

The bleak irony is that floods have always been part of the Indus story. This river has been responsible for nourishing civilisations for thousands of years and has carved out the very plains this nation stands on. But previous civilisations survived because they were built to cater to their needs. The Indus Valley cities mastered irrigation and storage. Mohenjo-Daro is one of the examples; it was built around 2500 BCE and is highly renowned for its planned streets and great drainage systems. The British-engineered canals continue to nourish a significant portion of Punjab.

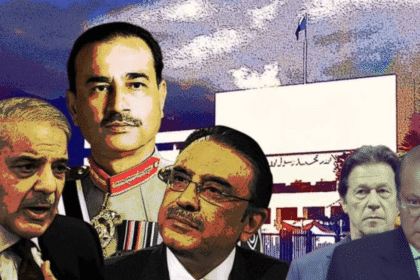

Post-independent Pakistan, however, became a victim of its own instability, collapsing within itself. The constant musical chair between civilian and army rule deepened its cracks. With every new government came a cycle of weaponising the inherited broken plans instead of fixing them. Every government pledged a dam; every opposition denounced it. General Zia championed Kalabagh. Benazir opposed it. Musharraf revived it. The provinces bickered like teenagers in the peak of puberty, full of relentless and unreasonable hatred. And the people — those who gave their trust and their hard-earned money through their taxes and donations — were left with nothing but longing for what could have been.

When the water came in 2022, sweeping away homes, schools, livelihoods and entire villages, the haunting silence prevailed. The silence of loss, of a nation conditioned to call its suffering “resilience”. We wear this patience like a medal, but perhaps it is quite the contrary and is closer to cowardice. Buzdil.

It’s a quiet acceptance of betrayal that has seeped into our skin, entrenched in our souls. We do not protest; we endure. We bury our anger deep inside as if it is haram for us to speak against injustice, which actually is quite the contrary.

But endurance is not salvation. Endurance will not stop the next flood nor the horror it follows. Without storage, without strategy, Pakistan’s monsoon will continue to be an announcement of destruction, cementing our fate. The people will keep giving their money, homes and lives, while our politicians argue in air-conditioned rooms in a mansion with too many rooms about whose province is more deserving, more threatened, or more wronged.

The dams that were never built remain monuments of absence — ghosts of what could have been. They are not just walls of concrete holding back the flood but haunting shadows etched by decades of mistrust and incompetent politics. And as the river keeps moving, so does time — and the clock is ticking. Still, the farmer waits, eyes caught between fragile hope and the same quiet despair he has endured.