For decades, the global internet was effectively American in governance and catered to Western ideology, practically shaping what freedom of speech looked like for the rest of the world. Although, from the perspective of many governments, the internet became a vector for potential foreign manipulation and even political destabilisation. Take for example China, who watched as Western propaganda poured in during the 1990s and early 2000s in opposition to the then dominant Communist Party. They observed, concluding if these platforms become essential to life, then emerging platforms won’t just connect people; they’ll help them organise. They won’t only host opinions; they will catalyse opposition. As a result, they curated a mirrored ecosystem: Baidu, WeChat, and Douyin—moulding narratives and embedding Party doctrine implicitly throughout the platform. Setting an example of a country constructing digital harmony, where disorder isn’t suppressed—’s never allowed to emerge.

Even countries such as America, which promote openness under the agenda of ‘free speech,’ exercise control over digital communication and interaction. TikTok suddenly gained traction as the third most used social media app and was a direct threat to American surveillance. The problem stems from the fear of the mere possibility that ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, could be compelled under Chinese national intelligence law to hand over user data or influence its recommendation algorithm at Beijing’s request. Beyond this, TikTok’s “For You Page” has the capacity to push content in accordance with its virality, often apolitical but occasionally subversive and radical, based purely on engagement patterns rather than conventional socio-political gatekeeping. As a result, its algorithm is often unpredictable. This is unnerving for policymakers, as much of the U.S. soft power infrastructure has historically flowed through media and entertainment: Hollywood, CNN, etc. If TikTok becomes the primary place where young people form opinions, and if it’s steered by an opaque foreign entity, that presents a cultural sovereignty crisis for the U.S. Ergo, the legislature pushed forth with the ‘Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act’ (PAFACA) in April 2024. This law mandated that ByteDance divest from the app within 270 days or face a nationwide ban (which temporarily ensued).

On the other end of the spectrum, Gen Z sees this for what it is—a hypocritical power grab. Many see TikTok not just as entertainment but as a platform to cultivate community. So when the government threatens to ban it, it feels personal. The backlash isn’t just practical (“How will I watch my favourite creators?”); it’s ideological (“Why are they silencing us?”). This is why during the height of the #TikTokBan discourse on Twitter/X, users flooded the site with memes mocking politicians for not understanding digital culture, trending hashtags like #LetUsDance, and sarcastic edits of Congressional hearings that went viral, turning the ban movement into a cultural joke. Resulting in TikTok itself becoming a symbol of resistance to perceived established control.

Ironically, this is ensuing in a country that spent years urging the global South, including China, to embrace the Western platforms in the name of openness. Now, finding itself unable to steer the narrative on platforms it doesn’t own, it turns to banning a platform with no real basis.

Notably, the growing alignment between X and the U.S. state highlights another dynamic: when ownership is favourable, sovereignty is less of a concern. That loss of influence is intolerable to a state that has long relied on American-owned platforms like X, YouTube, and Facebook to subtly promote its interests across the globe. This isn’t just hypocrisy. It reveals that digital sovereignty isn’t inherently authoritarian. It’s a condition all modern states are moving toward—keeping pace in a world where information has become both a weapon and a lifeline.

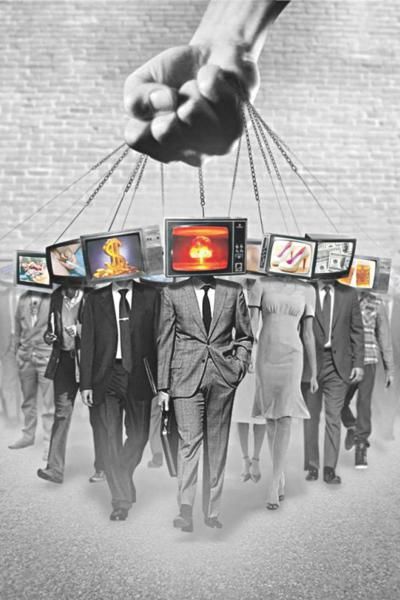

Overlaying all of this is the growing belief that traditional media no longer represents an impartial or credible arbiter of truth. ‘Today, Americans are divided roughly into thirds in how they view the mass media. Some 31% trust the media “a great deal” or “a fair amount,” while 33% say they do not trust it very much and 36% say they have no trust at all in the news media,states Public Relations Society of America Inc. Citizens now suspect their information environments are manipulated by media conglomerates, intelligence agencies, or hostile states. And often, they’re right. Billionaires fund newsrooms (Laurene Powell Jobs, through her Emerson Collective, purchased a majority stake in ‘The Atlantic’ in 2017). States use public broadcasters as propaganda arms (in promotion of nationalism, India’s prominent news channels,, such as ‘Aaj Tak’ and ‘Zed News,’ aired that Indian forces had captured Islamabad and destroyed Karachi’s port—ter debunked by the Press Information Bureau).

That loss of trust is the soft underbelly of the internet sovereignty movement. Regardless of platform, when people actualise how much of their thoughts, preferences, and even identities are being engineered by the government, they demand control.

Because of all of this, governments see justification for tightening the reins. As you see, media control, once the domain of newspapers and state broadcasters, has moved into the fabric of apps. As political scientist Shoshana Zuboff warned, surveillance capitalism didn’t just mine data; it shaped behaviour. Authoritarian states leaned into that logic, building surveillance networks fused with platform economies. Democratic states embedded power into regulation and “content moderation.” But the effect converges: all information is curated and cherry-picked to cater to an already curated national narrative. And in this new world, we must confront the real cost; truth itself may become nationally defined because the danger of digital borders isn’t just that they keep people out. It’s that they keep ideas in. A user in Beijing, Islamabad, or Washington may encounter entirely different realities due to censorship of overlapping viewpoints. Because of this we don’t just lose connection, we lose empathy.

This is the age of internet sovereignty, where nations treat the internet not as a shared space but as a domain to govern—like land, air, and sea—because if you control the platform, you control the narrative. Governments around the world are no longer content to simply regulate the internet; they want to own it.