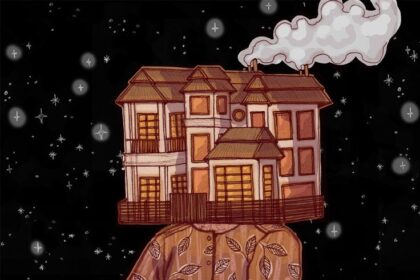

In the neighbourhoods of Pakistan, the lingering remnants of celebrations remain evident in each street in the form of dusty fairy lights tangled in the balconies of houses, which may have once been put on the occasion of Eid or a wedding. On another corner of the road, one can see the tattered and faded election posters once promising nationalist spirit barely stuck on walls in the midst of rising political tensions. Shuttered shops are seen to be draped with worn-out banners slowly decaying with the fleeting time. Despite the nature of decay enveloping these aesthetics in its embrace, these once-fragments of joy and hope still refuse to leave and surrender.

A question may still weigh on many people’s minds. The festivities are over. The music has faded. The guests have dispersed. But the fairy lights still flicker and shine on the balcony, making it seem as if they have forgotten how to let go. On the other hand, the torn election flyers are also still up on the walls of the streets. Some individuals declare these actions as yet another contributing factor to urban decay and a sense of neglect being shown by the residents living in those areas. So, the question arises: What is the real reason for not removing these objects?

Is it laziness? Sure, maybe according to a few people. Is it neglect? I don’t believe so. Rather, it seems to be a sense of longing and nostalgia that people are fighting against each day. The sense of yearning to go back to the simpler times, away from the commotion and obstacles of daily life. It is an insightful thought; the act of not removing, the preservation of objects around us that may seem insignificant to others but may remind individuals of some of the most exhilarating moments of their lives. It is not neglect, but a silent memorandum by individuals romanticising their lifelong memories and creating an emotion of sentimentality in each corner of their surroundings for as long as time will let them.

Banners with sayings like ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ swamping shops are not urban decay. The election posters plastered on walls are not a form of dilapidation. These specks of hope and triumph are a part of our culture. They are a quiet archive—a reminder of enthusiastic promises, aspiring dreams, and echoes of pride. They are a recollection of people’s experiences.

Wherever they go in their neighbourhoods, they see an old part of themselves locked away—on a weathered pavement, a chalk drawing on the walls of the street or playing on the balcony where the Pakistan flag they hung on the occasion of Independence Day still remains. A sense of familiarity comes from the act of not removing. A sense of belonging is felt that is difficult to overlook. These emotions are the ones that bind communities together, make people feel welcome and guide them when they are lost.

What lingers is more than a mere embellishment; it is a cultural testimony—a collection of the past evoking suppressed feelings of aspirations and exuberance in the country’s citizens.