“Please, bring me a cup of chai.”

“Chai?” The waiter frowned. “We’ve got English tea, madam.”

“Okay then, bring me a British tea.”

He gave me a cringe smile—one of those tight-lipped grins laced with polite embarrassment. I ignored the weight of his judgement and turned my attention to the menu of this very hip, very elite restaurant. It was dressed up in fancy colonial words: pink hummus, mango-lentil salad, crab-stuffed tacos. Fine.

But what hit me like a brick?

Double Trouble Brain Curry.

Spicy Lamb Rice.

Red Lentil Sauté in Sesame Oil.

Deconstructed Ras Malai.

That’s when it clicked: this place wasn’t just selling food—it was selling class.

And that’s where menu capitalism comes in.

It’s a simple phenomenon that pushes restaurants and food businesses to shed their native language, culture, and roots in order to appear more Western—and, therefore, more fine. This is why a dish as rich, layered, and spiced as biryani sells for dirt cheap, while risotto at the same price would be considered an insult. The judgement I got for ordering chai? That same cringe appears any time the Global South tries to speak in its own flavour.

The truth is, menu capitalism is a symptom of cultural imperialism.

As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o once said,

Cultural imperialism is the systematic destruction of a people’s culture, values, and ways of knowing.

It plants a deep-rooted inferiority complex that is teaching people to look down on their own traditions. Food and language are the first to be colonised because they are two of the most powerful expressions of culture.

Just erase language and food from our culture. What are we left with? A void, and that’s where the inferiority complex seeps in.

There’s a subtle, yet loud, hierarchy of dishes.

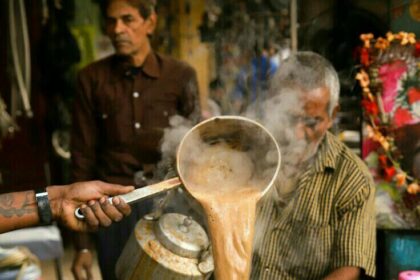

Global South cuisine is the cuisine of colour—vibrant, messy, spicy, and cheap.

Global North cuisine wears the crown of bon vivant—refined, minimalist, and expensive.

That’s why Pakistani food is described as cheap, comforting, and street-level.

French food is called elegant, light and aristocratic. It’s not food; it’s art.

It’s not just a menu but a map of power. Where the white man always wins because he owns the language and the financial might.

But it’s not just about what we eat; it’s also about what we call it.

Consider this: what if an elite restaurant in Karachi served lasagna, but instead of calling it “lasagna”, they labelled it “Teh-wala Cheesy Pasta” on the menu?

Would the burger crowd still order it with the same pride? Would it still feel “continental” enough to post on Instagram?

Probably not.

Because the dish didn’t change; however, the language did. And in that subtle shift, we see a deep-seated colonial hangover. A psychological condition where anything wrapped in local language or identity is instantly perceived as less refined, less elite, less worthy and less Instagrammable.

It doesn’t matter that both versions involve layered pasta, béchamel, and cheese. Lasagna sounds sophisticated; Teh-wala Cheesy Pasta sounds like it belongs in a desi suburb dhaaba.

And this shows the elephant in the room – consumer psychology. This reveals how consumer choices in elite circles aren’t just driven by taste; rather, they’re shaped by status signalling, language hierarchy, and cultural insecurity. When desi terms are applied to Western dishes, their value seems to drop. But when Western labels are applied to local food, prices and prestige rise.

The truth is, we seek validation from the West because we’re still hesitant to own our culture. And that’s the real tragedy. The boldness of our spices and the complexity of our flavours are, undoubtedly, our pride. Instead, we’ve convinced ourselves that they disqualify us from refinement.

The Way Forward

The only way to reclaim our culinary and cultural identity is to confront the colonial hangover head-on. And this begins with language. If we continue to treat Urdu as ornamental or informal, we will keep feeding the very system that trained us to be embarrassed by our own tongue. It’s the best time to teach children Urdu—not just to speak it, but to think in it, to write poetry, describe flavours in it and to live one’s true expression in it, freely. Let menus, textbooks, and kitchen stories break the shackle of mental slavery and return to the vocabulary of our soil. As Iqbal said,

Maghrib ke farzando se nafrat nahi lekin

Apni khudi se ho to nadamat hai zaroori.

(I bear no hatred for the West’s proud kin,

But shame is due when self is lost within.)

There must be a social media campaign on our “Inherited Prestige in Culinary Arts”. Prestige should not belong to French terms and minimalist plating alone. It should also belong to the skill of balancing spices, of slow-cooking qorma, of layering biryani like art.

Food festivals and culinary institutes must rise to the occasion. Celebrate the richness of Pakistani cuisine at local events. Create platforms where chefs are encouraged to innovate—not to imitate the West, but to build something truly our own. Let them create fusions, yes, but for joy, not for validation. And let them name these dishes proudly in Urdu. Imagine a world where khatti-meethi anday ki tart, tandoori jheenga pie, or adraki crème brûlée earn praise, not mockery.

The world doesn’t need another risotto. But one might need to know what taftaan tastes like when paired with burnt garlic butter. And it certainly needs to hear us say it with confidence.

We do not need to be more like them. We just need to stop being afraid of being ourselves to get others’ approval.